The assassination of Charlie Kirk on September 10, 2025, continues to dominate headlines. The Globe and Mail, a leading Canadian newspaper, ran the story under the headline: “Kirk’s debates turned politics into a spectator sport,” quoting experts who noted that the slain activist’s brand of confrontational videos had gained wide popularity.

The story carried an image of police taping off an area at Utah Valley University in Orem, Utah, where Kirk—the CEO of the conservative youth organization Turning Point USA—was shot and killed.

Media reports identified the suspect as 22-year-old Tyler Robinson, who turned himself in after evading authorities for more than 30 hours. Police said Robinson, angered by Kirk’s politics, fired from a rooftop more than 150 yards away before escaping a search involving helicopters, patrol cars, and foot teams.

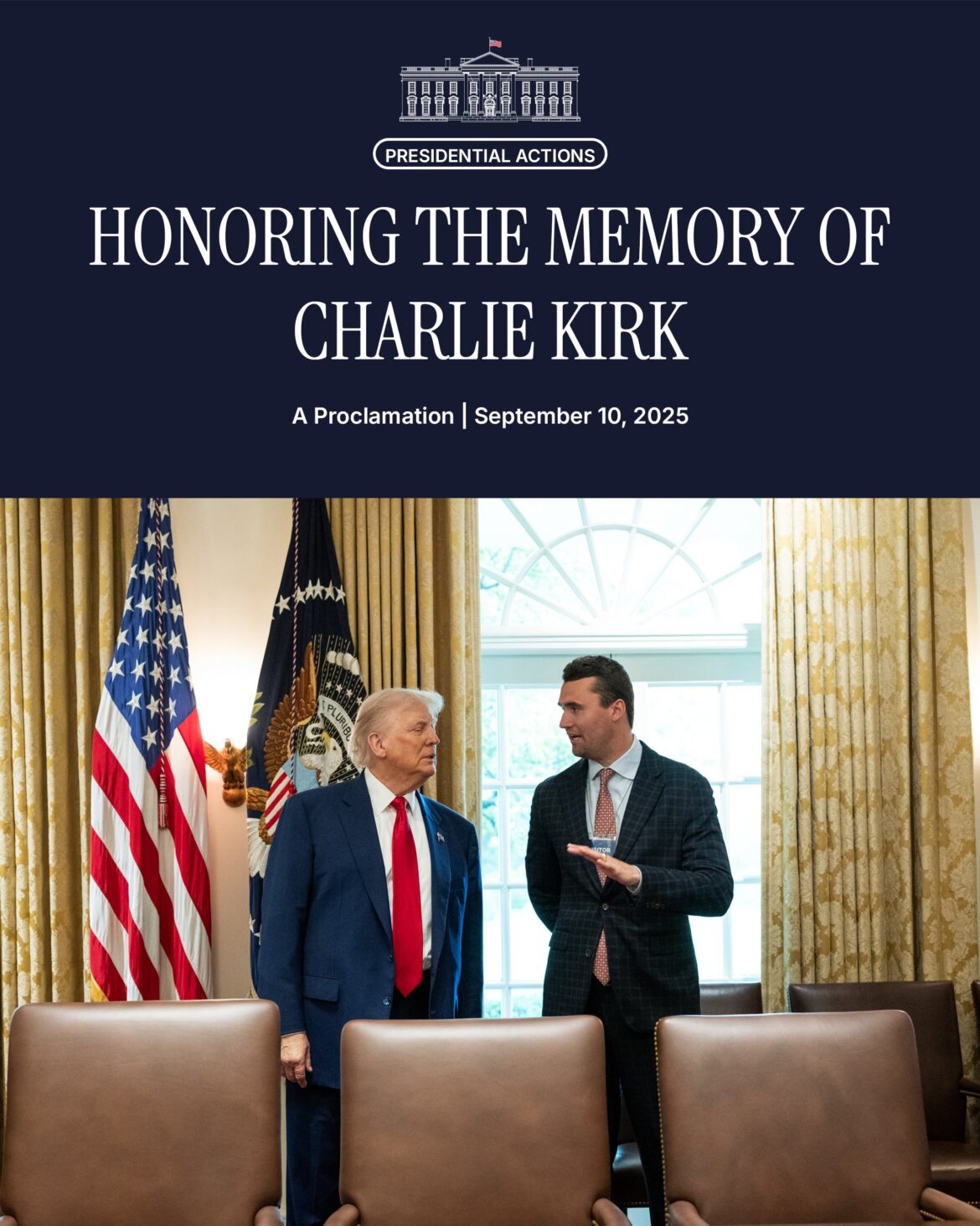

Former President Donald Trump announced that Kirk would be awarded a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, at a future ceremony.

The Globe and Mail’s Culture Reporter Samantha Edwards wrote that Kirk was sitting under a tent printed with the words “Prove me wrong” when he was shot. He was debating a young liberal TikTok creator on mass shootings involving transgender people, before an audience of about 3,000. The event was livestreamed across social media.

“In recent years, a crop of ‘debate me bros’ have engaged in conservative online culture,” the paper noted, describing Kirk, 31, as a MAGA influencer, Trump ally, and outspoken Christian who thrived on debates over gender identity, LGBTQ rights, gun control, Black Lives Matter, and immigration.

The Globe and Mail also reported that a University of Toronto professor had been placed on leave after posting about Kirk’s killing. Associate Professor Ruth Marshall, who teaches religious studies and politics, was put on administrative leave after an X account linked to her stated: “Shooting is honestly too good for so many of you,” and referred to Kirk as a “fascist.”

Ontario Minister of Colleges and Universities Nolan Quinn condemned the post, saying: “Universities and their professors are supposed to foster critical thought, respectful debate, and safe learning environments—and this professor’s violent rhetoric flagrantly flies in the face of that.”

The university said it acted independently and informed the government afterward, declining further comment.

Columnist Ezra Klein wrote that “a free society is built on the right to engage without fear of violence,” warning that political violence is contagious. He recalled the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Robert F. Kennedy, and Medgar Evers in the 1960s, as well as attempts on George Wallace, Gerald Ford, and Ronald Reagan in later decades.

“These assassins and would-be assassins had different motives, politics, and levels of mental stability,” Klein noted. “When political violence becomes imaginable—either as a tool of politics or a path to fame—it spreads heedlessly.”

The New York Times reported that Kirk’s assassination has intensified security fears among U.S. lawmakers. Many canceled outdoor events, saying the security situation had become untenable.

“People are scared to death in this building,” said Representative Jared Moskowitz, a Florida Democrat and target of a 2024 assassination plot. “Not many will say it publicly, but they are running to the speaker talking about security—and that includes a lot of Republicans.”

The paper added that Trump’s announcement of Kirk’s death on Truth Social appeared on lawmakers’ plane screens, leaving both Republicans and Democrats visibly shaken. Some Republicans, however, blamed Democrats for fueling violence. Senator Josh Hawley of Missouri said, “We have had three assassinations, or assassination attempts, of major political leaders in the last 18 months. All the targets are one persuasion, and all the shooters are one persuasion.”

Political violence is not unique to the U.S. In India, Prime Ministers Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi were assassinated while in power, as was Punjab Chief Minister Beant Singh. Finance Minister Balwant Singh was ambushed and killed in Chandigarh.

Pakistan’s history is also marked by political assassinations. Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan was shot dead at a rally in Rawalpindi in 1951. In 2007, Benazir Bhutto, a two-time Prime Minister, was assassinated in a gun and bomb attack after a rally in the same city, months after surviving another attempt in Karachi that killed 139.

Military ruler President Mohammad Zia ul Haq died in a mysterious 1988 plane crash, spawning conspiracy theories. Pakistan has also seen repeated coups, from General Ayub Khan’s takeover in 1958 to General Pervez Musharraf’s coup in 1999.

In 2022, former Prime Minister Imran Khan survived an assassination attempt during a protest march. He was shot in the leg in what his aides called a clear attempt on his life. Pakistan remains plagued by instability, with Rawalpindi often at the center of political violence.

Difference of opinion is a cornerstone of democracy. But when dissent escalates to assassination, the democratic process itself is undermined. Despite global progress, political assassinations persist across both authoritarian and liberal democracies, reminding societies of the fragility of civility in political discourse.

My Musing:

On Meeting a Sikh Journalist

On professional assignments outside Chandigarh, whenever I introduced myself as Prabhjot Singh from The Tribune, the question often came: “Are you from Punjabi Tribune?” Perhaps implying that a Sikh cannot write in English. I usually laughed off such queries. There could be many reasons for such a question. Not many Sikhs took to newspaper reporting, especially as Staff Correspondents of The Tribune.

I had gone to Pakistan to cover the World Cricket Tournament for the Reliance Cup, accompanied by other Indian and foreign journalists.

At the National Stadium in Lahore, on the eve of Pakistan’s match against England, Pakistani players were at the nets. We were engrossed in a discussion when I felt someone touch my shoulder. I turned and saw none other than Pakistan’s leg-spinner, Abdul Qadir.

“Sardarji, sada kaptan tuhanu bulanda je,” (Sardarji, our skipper is calling you), Qadir said, pointing towards the Pakistani tent where Imran Khan sat in a chair. I told Qadir I would come in a few minutes. Imran Khan was all smiles as he looked me over.

He asked, “Sardarji, Punjabon aye ho?” (Sardarji, have you come from [East] Punjab?)

“Ji,” I replied. “Match dekhan aye ho ke ghuman phiran aye ho?” (Have you come to watch matches or for sightseeing?)

“Matchan layi aya haan.” (I have come for the matches.)

“Ki kam karde ho?” (What do you do?)

“Main ik akhbar wich kam karda haan.” (I work for a newspaper.)

“Aacha; tusee taan te pher ik sahafi ho?” (I see, then you are a journalist), he said, and started laughing.

He hugged me and said: “Kasam Khuda di, aaj main pehli var koi Sikh sahafi takya je.” (By God, I have seen a Sikh journalist for the first time.)

“Sikh lok te vaise ve kaat hi cricket khed de ne. Par Sikh sahafi dekh ke tan barri hairangi hoi je. Koi sewa hoi taan dasna,” he added. (Not many Sikhs play cricket. But seeing a Sikh journalist is a greater surprise. Let me know if I can be of any help.)

Afterwards, throughout the tournament, whenever Imran Khan saw me, he would wave and shout, “Sardarji, Sat Sri Akal.”

Disclaimer: The opinions and views expressed in this article/column are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of South Asian Herald.