Sriram Emani is an actor, filmmaker, and cultural entrepreneur whose work bridges technology, storytelling, and heritage.

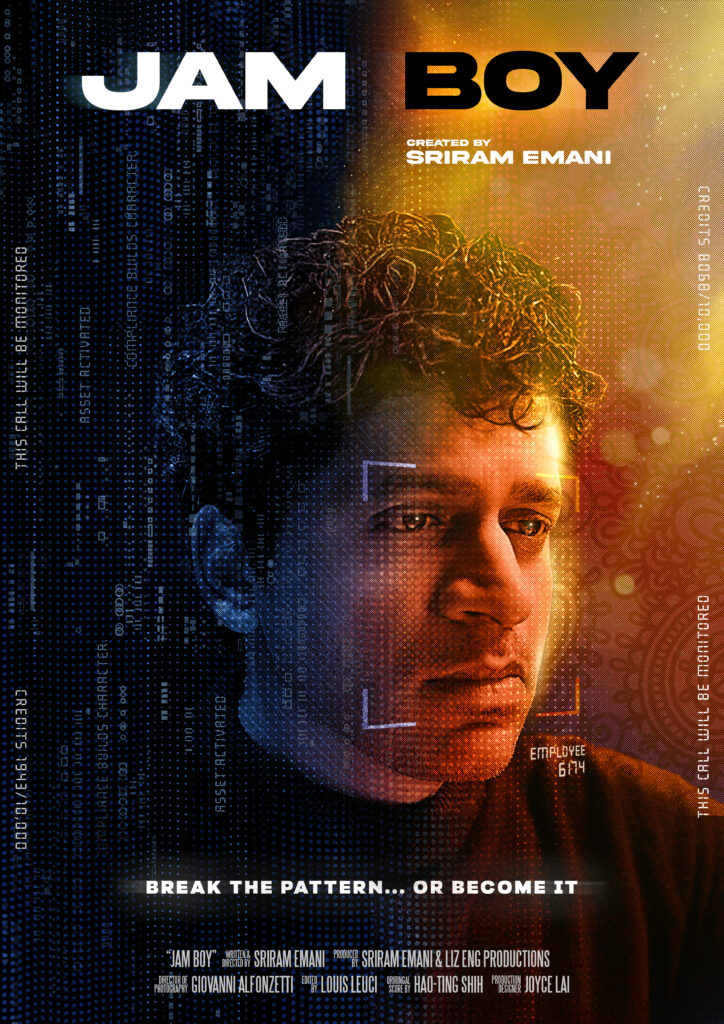

The premiere of his film Jam Boy will take place on February 15, 2026, at the DC Independent Film Festival, Washington, DC’s oldest film festival. The screening is expected to draw a diverse audience from across the region, including leading artists and entrepreneurs from the South Asian community. Among the dignitaries attending are Anuradha Nehru, founder of the award-winning Kalanidhi Dance; tech entrepreneur Murali Yellepeddy; and Iravati Damle, Head of Global Policy Operations at Zoom, among others.

In Jam Boy, food, family, and quiet acts of defiance intersect to tell a deeply personal immigrant story that resonates far beyond its immediate setting. In this exclusive interview with SAO, the filmmaker reflects on using cooking as a vessel for memory and resistance, the rare experience of sharing the screen with his own mother, and the conscious choice to keep the film’s critique universal rather than overtly political. The result is a work rooted in lived specificity, yet expansive in its emotional reach.

A graduate of IIT Bombay and MIT, where he was a Siebel Scholar and a Tata Fellow, Emani brings analytical depth and artistic vision to his filmmaking. He is the founder of IndianRaga, the global arts platform that has collaborated with more than 5,000 artists and garnered over 500 million views worldwide. IndianRaga performances have opened for Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the World Government Summit and at the landmark Howdy Modi event in Houston.

As an actor, Sriram has appeared in projects including Chosen Family, alongside Heather Graham, and the CBS series Matlock. He has also delivered a TEDx talk on his IndianRaga journey. Through his work, both on screen and off, he continues to champion stories that connect tradition, innovation, and the evolving South Asian narrative.

Jam Boy uses food not just as nostalgia, but almost as resistance. Why did you choose something as intimate as cooking to carry such emotional and political weight?

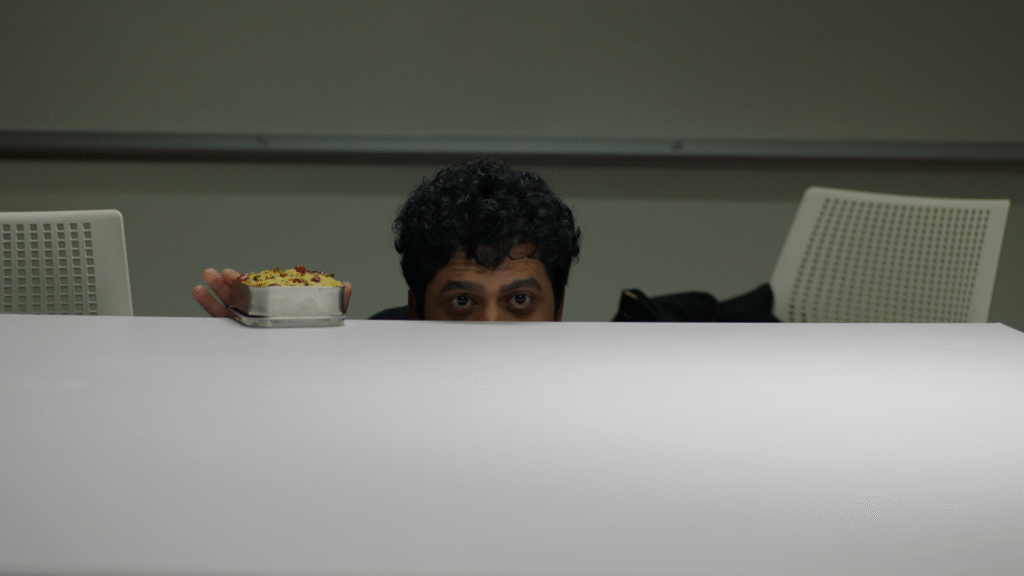

Food is one of the last things immigrants hold onto without permission. You can change your accent, your clothes, even your name, but the way you cook and the recipes your parents taught you live in the body. In Jam Boy, tamarind rice is not just comfort food. It represents continuity, dignity, and cultural selfhood. In a world where the character is constantly being evaluated and optimized, cooking becomes an act that is not about productivity or performance. It is about care, ancestry, and belonging.

Food is also one of the easiest ways to share culture across differences. You do not need a long explanation or history lesson. You offer a bite and suddenly someone understands a part of your world. The moment Sofia enjoys the tamarind rice is powerful because he feels the joy of someone outside his culture genuinely connecting with something deeply personal. That emotional bridge is much harder to show through dialogue, but food makes it immediate, warm, and human.

Your mother plays your mother in the film. How did having a real parent on screen change the emotional truth of those scenes?

It changed everything in both beautiful and challenging ways. Some of the interactions in the film are not true of my mom and I in real life. She has never had to tell me to break the pattern. If anything, I have broken too many patterns already. So for us to perform that scene, we had to truly step into our screen characters and imagine a relationship dynamic we have never actually lived. That was an acting challenge for both of us.

It was also funny because before COVID I visited my parents in India multiple times a year, and after COVID my parents moved to the US to be with me. So for our characters to carry the emotional weight of not having met for five years was something we really had to imagine and build together. At the same time, having a real parent simplified production in unexpected ways. Childhood photos were easy to source. I could also shape the writing around her personality. The Telugu rap, for example, grew out of knowing her musical background and sense of humor. In the end, working together created joyful memories we will carry for life. My mom being part of my debut short film felt both auspicious and fun.

The film avoids naming specific corporations or systems, yet it feels very real. How did you balance universality with lived specificity?

It was a deliberate choice not to name specific companies or policy systems. The story is not about blaming a particular institution. It is about placing equal emphasis on the internal journey of those navigating these systems. When you remove direct labels, audiences are more able to place the story in their own context. Friends in India told me it felt relevant even for mainland Indians. Others saw parallels in different parts of South Asia and beyond. That universality comes from emotional truth rather than political specificity.

Many diaspora stories focus on visible struggles. Jam Boy feels quieter and more internal. Why was it important for you to tell an inward story?

There is already a lot being said about visible challenges, and those stories are important. What we do not see as often are the internal forces that shape how people respond to those challenges. The quiet self-editing, the desire to be perfect, the pressure we place on ourselves to be endlessly grateful and productive. Those internal patterns influence outcomes just as much as external barriers.

I wanted to explore the idea that we also have to show up for ourselves. We cannot always wait for systems to change first. Sometimes change begins with recognizing the patterns we have absorbed and deciding which ones still serve us. That inner shift can be just as dramatic as any external conflict, and sometimes even more freeing.

Washington, DC is a city shaped by policy and power. What does it mean to premiere this story there?

It feels especially meaningful because these conversations are happening in DC every single day. Immigration, belonging, and opportunity are not abstract topics there. They are part of daily debate and decision making. Premiering Jam Boy in that environment makes me feel that the film has found an audience that understands the nuance of these issues.

It also tells me that the film struck a balance. It is not a lecture and it is not a fantasy disconnected from reality. It is a human story that resonates with people who engage with these themes professionally and personally. That makes the premiere feel both timely and affirming.

The score plays a major role in shaping the atmosphere. What were you hoping the music would convey?

I wanted the score to feel like an inner current rather than a loud emotional cue, and I found the perfect partner in Jude Shih to design it. Jude used digital and electronic textures to give parts of the soundtrack a slightly mechanical, almost video game-like feeling. That choice reflects the system-driven, algorithmic environment the character lives in.

When Poornima’s flute enters, it brings a human and cultural layer that cuts through that digital soundscape. That contrast between machine-like textures and a traditional instrument mirrors the tension in the character’s life. With my own musical background and years of leading IndianRaga, the score was no doubt very critical for me and I treated it as its own character in the film.

You have produced hundreds of IndianRaga videos across multiple countries. How did that experience shape how you made Jam Boy?

IndianRaga trained me as a producer in the real world. We made hundreds of videos across five countries, often with limited resources and tight timelines. That teaches you to anticipate problems and adapt quickly. That muscle was very useful on Jam Boy. For example, when we struggled to secure the right office location, we had to rethink production design challenges on the fly. We also had to change the venue of the dance shoot at the last minute to make it logistically feasible.

Time also flies on set, and knowing how to stay disciplined with the shot list, prioritize what matters most, and move on at the right time is something I learned in the early hustle days of IndianRaga. That experience helped us stay efficient without losing emotional depth.

What do you hope South Asian audiences, in particular, take away from Jam Boy?

I hope they feel that staying rooted in culture and tradition is not just something we do to please elders. It is one of the greatest gifts we can give ourselves. The deeper your roots, the stronger and taller you can grow. Culture gives you emotional grounding in a world that is constantly shifting.

At the same time, I hope audiences also find moments of joy, humor, and recognition. Jam Boy is not only about pressure and conflict. It is also about warmth, family, music, and the small things that make life meaningful. If people leave the film feeling both seen and uplifted, that would mean a lot to me.