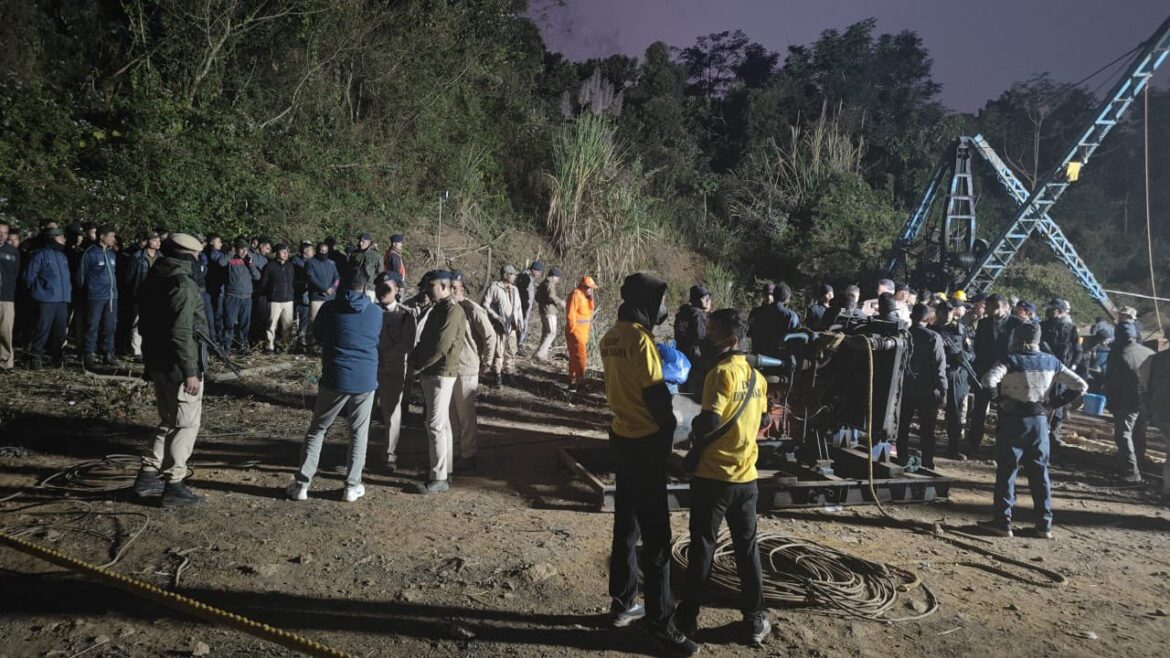

Umrangso’s rat-hole mine flooding in January 2025, which trapped nine workers, underlined how quickly unauthorised extraction turns fatal. Similar incidents across the North East show that a ban without routine detection and enforcement becomes symbolic. Assam’s Standard Operating Procedure (SOP), issued months later amid judicial scrutiny, is a step towards institutionalising prevention, but it will matter only if it also delivers accountability and rehabilitation.

The Gauhati High Court’s suo moto intervention in January 2025 kept the issue in focus and the subsequent orders and proceedings have also raised the stakes for criminal accountability, including imposition of ‘murder’ charges on responsible to prevent such accidents. The directions of the Gauhati High Court do not offer a “closure moment,” nor does the SOP, however, these serve as a reminder that accountability is a concern, and prevention and rehabilitation are not being implemented.

In December 2025, Assam issued an SOP to move from sporadic crackdowns to a standing district pipeline for detection, verification and enforcement. It creates a District Mining Control Committee (DMCC) chaired by the District Commissioner, with officials from mining, police, forest, labour and revenue, and scope for local consultation where relevant.

SOP mandates periodic physical or drone surveys, with classification of the mining activity as either legal or illegal. These shall be referred to the Joint Field Action Team (JFAT) for on-site verification. After which, the District Geology and Mining Officer files an FIR, the police act, and the DMCC ensures shutdown and closure using District Mineral Fund support, where offenders are unknown or unable to pay.

Assam’s approach follows a wider administrative trend of using district task forces and technology to curb illegal mining. Haryana, for instance, has relied on drones and satellite imagery with district-level task force monitoring. Meghalaya, however, shows the limits of enforcement alone: even under prolonged court monitoring and committee oversight, reports continue to flag illegal rat-hole mining and transportation. Assam should read this as a warning that illegality adapts unless enforcement is paired with worker transition and transparent outcomes.

First, DMCC-led enforcement should be paired with a worker transition plan. Every verification drive should include basic worker identification and mapping of labour intermediaries, so rehabilitation is not an afterthought. The District Labour Officer should be tasked to connect identified workers to skilling and placement pathways within a fixed timeline, with jobs that offer comparable local wages, reducing the incentive to return to unsafe pits.

Second, Assam should notify minimum safety and liability conditions for any permitted mining activity: worker registration, basic insurance, emergency response plans, minimum safety equipment, and clear contractor liability. DMCC’s periodic classification should include a compliance review against these conditions, and it should push mechanisation and safer methods wherever feasible to reduce human exposure to high-risk work.

Third, the SOP’s upward reporting should be matched with public-facing transparency. Each district should publish a quarterly public scorecard covering surveys undertaken, sites verified, closures completed, FIRs filed, and District Mineral Fund spending on closure and safety measures. Assam’s SOP will save lives only when enforcement is paired with time-bound worker transition at comparable wages and a public record that makes prevention measurable and politically unavoidable.

Disclaimer: The opinions and views expressed in this article/column are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of South Asian Herald.