Sometimes, life delivers a humbling reset. Last week, I traveled eight hours north from Colombo to Jaffna, Sri Lanka, with The HALO Trust, the world’s largest humanitarian demining organization. What I encountered there was a stark reminder of how much of what we call success is shaped by the lottery of birth: where we are born, which families raise us, and which countries we call home.

I joined HALO’s Board of Trustees earlier this year. Like many, I had known the organization primarily through that iconic 1997 image of Princess Diana walking through a minefield in Angola. I knew the photograph. I did not truly know the work.

Now I do.

Since its founding in 1988, when Soviet troops withdrew from Afghanistan leaving behind a devastating landmine crisis, HALO has operated across more than 32 countries and territories. In Sri Lanka alone, where HALO has worked since 2002, the organization has cleared over 300,000 landmines and, in total, more than one million explosive items.

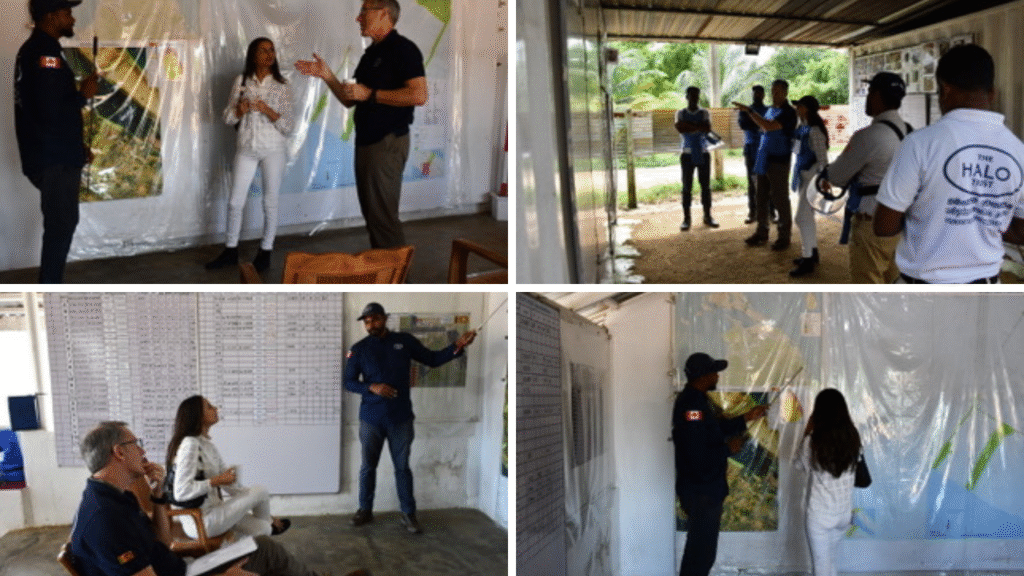

The Northern Province, where I spent a few days with HALO’s teams, bears the deep scars of Sri Lanka’s decades-long civil conflict. HALO Sri Lanka has had a staff ranging from roughly 850 to more than 1,200, making it one of the region’s largest employers. Over 99 percent of positions are filled by local recruits. Many of these deminers are clearing the very land from which they were once displaced.

What I witnessed challenged every assumption I held about post-conflict reconstruction.

Decades of disrupted education mean hiring locally requires a fundamentally different approach. Training is not a single induction but continuous, rigorous preparation and development.

New deminers must learn to identify seventeen different types of landmines, as well as other explosive hazards: anti-personnel mines, anti-vehicle mines, unexploded ordnance, and improvised explosive devices. They must learn how to locate and excavate them precisely and safely, and they are tested against rigorous standards before being allowed to join an experienced team operating in the minefields.

However, even for the most experienced deminer, training does not stop there. There is daily refresher training on specific drills before teams move into their clearance lanes, while more extended refresher training takes place at frequent intervals throughout the year. Those operating more specialist equipment conduct refresher training every three months. It is a continuous process.

In fact, 42 percent of HALO Sri Lanka’s deminers are women, including at every level of leadership in the field. A manual demining team commander will lead a team of eight. One of those will be a highly trained team medic, supported by a minimum of two other medically trained personnel, including the commander and 2IC. Safety is never assumed; it is engineered into every operation.

The terrain itself demands innovation. Minefields hidden in dense jungle, along coastlines, on islands, buried among field fortifications and earthworks, and submerged in lagoons require novel solutions and, at times, specialist equipment. This includes a bespoke, first-of-its-kind amphibious excavator provided by the United States Government at the end of last year. The Sri Lankan teams have developed new standard operating procedures for using it to clear mines from waterlogged environments. These will now be shared across HALO’s global operations, including in Ukraine, which faces similar challenges from flooded minefields caused by ruptured and damaged dams.

This is what locally led development looks like in practice. This is impact beyond headlines.

I met families finally able to return home after decades of displacement. I saw the quiet pride of people reclaiming land that once threatened their lives. And I learned that HALO is constantly developing its staff’s skills and preparing them for a life beyond demining, once they have completed their demanding and dedicated work to remove the very last explosive hazard from the soil of Sri Lanka.

HALO is often remembered for one photograph from the 1990s. It deserves to be known for the thousands of lives it has protected every day since.

If you care about stability, about rebuilding after conflict, about dignity and safety as foundations for everything else, I urge you to learn more about The HALO Trust. Support takes many forms: funding, partnerships, advocacy, and conversation.

Some organizations change landscapes. Some organizations change lives. HALO does both.

Disclaimer: The opinions and views expressed in this article/column are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of South Asian Herald.