China, once known for churning out cheap products for Western shelves because of its cheap labour, is weighed down by a deep property slump and a consumer recovery that has never quite arrived. With Beijing turning inwards, the question before us is how India can pursue a generation-defining economic opportunity with the very country that is its strategic competitor, where China’s growth model is being forced to change.

The answer lies in the economic and strategic situations unfolding in and around China. Firstly, in economics, Gross Domestic Product (“GDP”) consists of four components: consumption, government expenditure, investment, and net exports. Out of these, consumption and net exports play a major role in any economy. According to the World Bank, exports account for 20% of China’s GDP, whereas domestic consumption accounts for around 40%. On the other hand, in major economies such as the United States, domestic consumption accounts for around 70% of GDP, and even India’s consumption accounts for 65% of its GDP.

This weak domestic demand in China is not accidental but deliberate. China has, for years, kept its currency, the Renminbi (“Yuan”), weak through a “managed float,” where it does not allow the Yuan to fluctuate more than 2% against a fixed level, to make its exports competitive. In the meantime, China has massively invested in infrastructure to boost its GDP, as total investment as a share of GDP grew to a whopping 40% in 2024.

However, as Trump administrations undermined global trade, and the world became more cautious of Chinese goods—as evidenced by the EU and the US imposing tariffs on Chinese EVs, among other things—the Chinese Communist Party, if it is to meet its growth target of 5%, will have to give its consumers more purchasing power. Beijing has sought to mitigate this with the “Dual Circulation Strategy” (DCS), introduced in 2020 by General Secretary Xi Jinping and incorporated into the 14th Five-Year Plan in 2021, with the main focus being increasing domestic consumption and shielding against geopolitical tensions.

But a Fed note titled “Is China Really Growing at 5 Percent?” by the Federal Reserve (“Fed”), which came as the 14th Five-Year Plan is set to conclude this year, showed that although production remained steady, consumption was weak. This was particularly worsened by the property sector crisis in China, where three-quarters of Chinese household wealth is tied up.

Along with domestic policy shifts, over the years China has done many things to sustain its GDP growth, from projects like the Belt and Road Initiative (“BRI”), which aimed to develop infrastructure primarily in developing countries. This provided China with a threefold advantage: first, sourcing raw materials from Chinese companies; second, jobs for Chinese engineers and workers; and third, giving the Chinese government immense leverage over those countries and extracting strategic concessions from them, as seen in the cases of Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and many countries in Africa.

However, there are other reasons China would relax, if not entirely unpeg, the Yuan, mainly tied to its ambition of making the Yuan a dominant currency in international trade, replacing the US dollar. In order to realise this goal, the Yuan would need to be stable and market-driven, as no central bank would hold massive reserves if it believed the Yuan could be manipulated for domestic political gain. Moreover, a stronger Yuan would not only increase consumer purchasing power but also increase domestic demand, which would provide an alternative market for Chinese-produced goods in the dawn of protectionism in global trade and help address the wealth crisis, which was significantly impacted following the property sector crisis in China.

Moreover, the International Monetary Fund (“IMF”) urged China to speed up structural reforms. The IMF said, “The key policy priority for China is to transition to a consumption-led growth model, away from an overreliance on exports and investment.”

In the midst of these tensions and the Chinese slowdown, India has a unique opportunity to leverage its large workforce and economic scale. Rather than focusing solely on filling market gaps left by China’s retreat or protectionism, India should strategically position itself to serve the rising Chinese consumer as per capita incomes grow. When, as appears likely, the CCP relaxes its currency controls, Indian products could become more affordable for Chinese consumers, replacing those priced out by China’s rising labour costs.

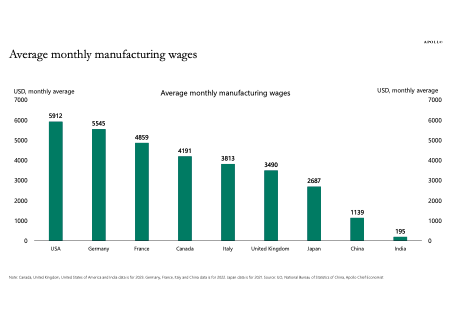

Past trends support this. In the 1980s, Deng Xiaoping’s reforms made China the world’s manufacturing hub as its labour costs undercut those of the US. Now, as China’s labour prices rise, India is positioned to step in and benefit. According to new data released by World of Statistics from U.S. News & World Report, India is now the most cost-effective country for manufacturing, overtaking China and Vietnam.

Now, the dogma in Delhi is that China is a geopolitical rival to India, and that is true to a great extent. Given that it is an expansionist state, China has, since our independence, not only tried to undermine our territorial sovereignty but has continued to do so with all of its neighbours. However, India has demonstrated through the Galwan and Doklam incidents that it can resist China militarily if necessary, should a short conflict take place. Besides this, the Himalayas prevent any large-scale war between the two Asian giants. Additionally, India’s position on the South China Sea is “clear and consistent,” as put by MEA Secretary (East) P. Kumaran, that India considers it a part of the global commons and supports freedom of navigation, as almost 55% of India’s trade passes through it, as reported by The Diplomat.

Thus, groupings like the QUAD that seek to contain China’s military expansion are essential for India to secure its own economic interests. An unaligned India would be vulnerable to Chinese coercion and unable to build deep trade relations. A foreign policy that prioritises economic interests rather than confrontation is sound, given that India has no territorial claim in the South China Sea. It would suffice that the South China Sea remains free for trade; however, entangling ourselves with territorial claims in the sea would not be in India’s interest.

India’s course of action, therefore, has to be both strategic and selective. New Delhi should treat the Chinese consumer not as an afterthought but as a defined market, using a clear export strategy that prioritises sectors where India already has an edge and where Chinese demand is likely to remain resilient despite the property-led wealth shock and still-depressed household consumption.

This means tasking the commerce and external affairs ministries with an explicit China-facing export strategy, including targeted market-access negotiations and standards cooperation in a few high-value product lines, while simultaneously ring-fencing critical technologies and security-sensitive sectors. At the same time, India should use forums from the WTO to regional platforms to push for a rules-based response to any renewed surge of underpriced Chinese exports that stems from delayed rebalancing. If India plays its cards well, it can turn a potentially destabilizing neighbor’s slow and politically fraught transition into an opportunity.

Disclaimer: The opinions and views expressed in this article/column are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of South Asian Herald.