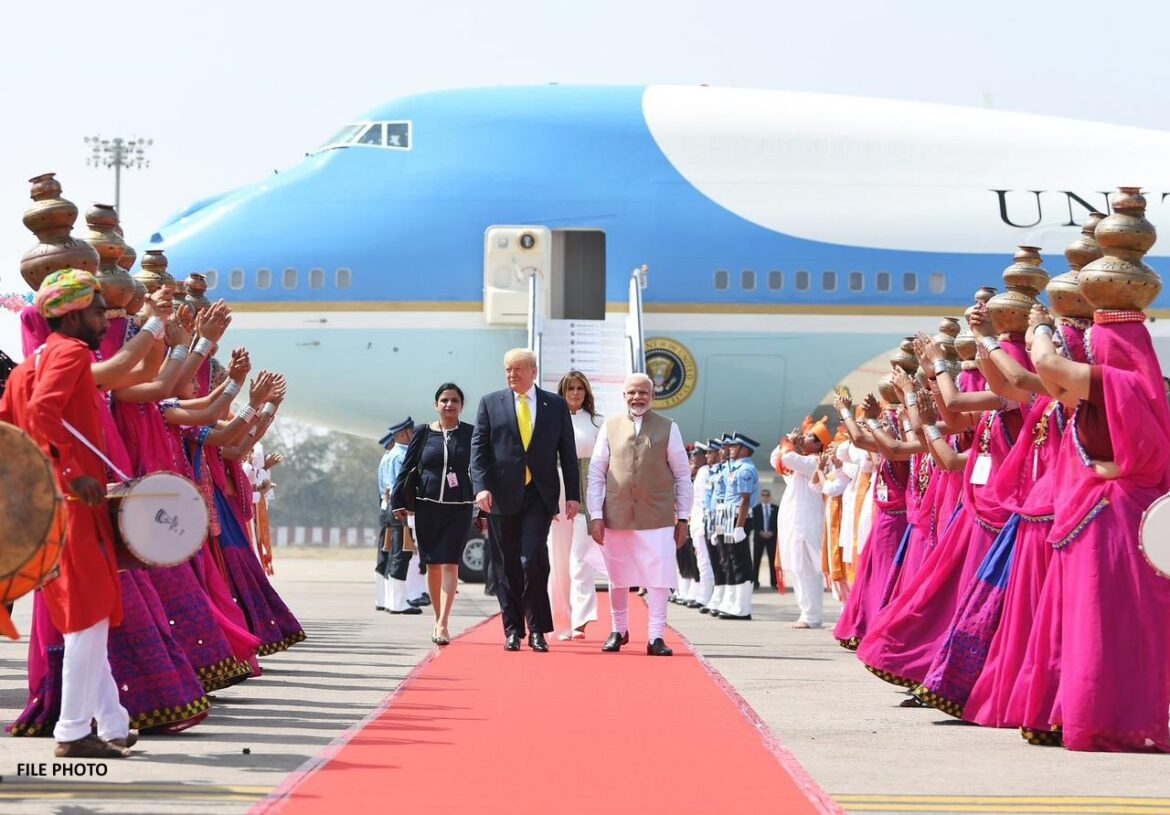

Clearly, some political and media pundits are looking way beyond their nose while talking about the visit of President Donald Trump to India, coinciding with the Quad Leaders Summit.

Complicating matters were reports of the American leader visiting Pakistan in September, which were quickly shut down by the White House. And now, some speculation about whether President Trump will make at least a stopover in Islamabad on his way to or from India for the Quad.

In all the initial hoopla on the subject, there is a tendency to forget one major component: the last word on President Trump’s trip to Asia has not even been whispered in the corridors of Washington DC. More importantly, no one from the outside dictates a President’s itinerary.

Not many remember that it was President Trump who pushed the Quad in a meaningful way during his first term as President, and with necessary backing from the then Prime Minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe. The Trump-Abe friendship and partnership no doubt revived the Quad from wilderness into some sort of meaningful cooperation between the United States, Japan, Australia, and India – all with a keen eye on China, which was increasingly flexing its muscles in the Indo-Pacific. Beijing and the Indo-Pacific alone were not the main points of attention: China was making, and continues to make, troublesome noises in the South China Sea, where as many as six nations have competing claims in an area supposedly rich in oil and natural gas.

It is not an exaggeration to say that Trump 2.0 dealt a body blow to many nations, including from the Quad, over threats of tariffs, taxes, and secondary tariffs, with Washington hammering away especially at Japan with reciprocal tariffs of 24 percent, an additional 25 percent on automobiles and parts, and 25 percent on steel and aluminum.

All of these were perceived as “disastrous” for Japanese businesses, with automakers from the East Asian country seen as bearing the brunt of losses: for fiscal 2026, Toyota and Honda are estimating profit losses of up to 35 percent and 70 percent respectively. Both Washington and Tokyo are continuing serious talks on a trade deal but still remain far apart. Or, as President Trump put it, “I’m not sure we’re going to make a deal. I doubt it with Japan. They’re very tough. You have to understand they are very spoiled.”

Like Japan, India too is in the midst of high-profile negotiations for a trade agreement, even if every now and then word comes out of a possible “mini deal” or that an accord on agricultural products has actually been reached. Japan, through its Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, has maintained that in a “battle for our national interest… we will not be underestimated,” an unmistakable reference to the primacy of cultural norms involving rice and agriculture.

The same holds good for India as well, where agriculture plays a pivotal role in society and politics. It is pointed out that in the current negotiations, Washington has been pressing New Delhi to open up on a range of American products, including dairy, poultry, corn, soybean, rice, wheat, and citrus fruits; and that India is hanging tough on imports of corn, dairy products, and wheat but is amenable to more access for dry fruits and apples.

But it is not all economics and talk of tariffs that is souring the environment. For instance, every now and then President Trump and his Cabinet officials bring up strategic aspects of alliance politics, pointing out how it is so “one-sided” when it comes to Japan. The United States, President Trump maintained recently, “pays hundreds of billions of dollars to defend them (Japan), but… they don’t pay anything,” a line of thinking and argument that does not sit well in Tokyo.

It is no secret that Washington would like its allies in the Asia-Pacific to cough up 5 percent of GDP spending on the military, more on the lines set by NATO; and in the case of Japan, the Pentagon would like to see a hike to 3 percent of GDP. But Tokyo insists it will decide the numbers on its own.

In traveling halfway around the globe for a Quad meeting in India, President Trump and his advisors would want to make the most out of the travel, and at the same time make sure that the correct political signals are sent along the way to allies and adversaries. In the case of the American President, adding or skipping capitals and making pit stops along the way will have a message of its own.

Disclaimer: The opinions and views expressed in this article/column are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of South Asian Herald.