Every time there is a new dispensation in Washington, D.C., there is always a debate in the Asia-Pacific or Indo-Pacific on the all-too-important issue of commitment: will the United States remain committed and engaged in a part of the world that is crucial to the strategic and economic interests of all involved? For an administration that seemingly started off well, through its Defense Secretary, Pete Hegseth, by stressing that the United States is there to “stay,” Washington is now raising difficult questions and choices for its Asian friends and even close allies like South Korea and Japan.

Much of the apprehension has to do with an emphasis on one aspect of American foreign policy: the preeminence of tariffs in trade that President Donald Trump frequently talked about during the course of the political campaign in 2024. The so-called distortions in the balance sheets of trade, it was surmised, could be set right if only the United States started punching its weight through tariffs that soon witnessed retaliation. The levying of tariffs also brought about a thinking that the additional income could go a long way in coming to terms with the overall deficits, now pegged at around US$37 trillion.

The problem with the tariff imposition and the rhetoric that came with it undeniably had its fallouts in the international system, with friends turning into adversaries and adversaries suddenly seemingly on the same page. When President Trump slapped 25 percent on India even as trade talks were going on, it came as a major jolt. But a bigger blow was dropped by way of secondary sanctions—another 25 percent for buying Russian oil and, by extension, bankrolling Moscow’s war in Ukraine. And with this also came the allegation that New Delhi was profiteering from the third-party sale of Russian oil, a charge firmly rejected by New Delhi.

India has consistently maintained that its imports of oil from Russia are only within the established guidelines and that it was Washington that was encouraging the imports with a view to maintaining price stability in international markets. But soon there were those who were making the point that Washington’s ire had little to do with India importing 40 percent of its oil needs from Russia or buying a lot of military hardware from that country.

It perhaps had to do with New Delhi refusing to go along with President Trump’s assertion that he mediated an end to the short India-Pakistan war in the aftermath of the Pahalgam terror attack on innocent tourists by Islamabad-backed terrorists. Every time Trump or Official Washington put out the line that the American President was responsible for ending the conflict, New Delhi came back with a denial. Not once was the assertion left to stand.

“Silence emboldens the bully,” said China while ripping apart American tariffs on India, going on to make the point that Asian powers should move beyond competition and build “strategic mutual trust.” Or, as China’s Ambassador to India put it, “… the US has long benefited greatly from free trade but now uses tariffs as bargaining chips to demand exorbitant prices from various countries. The US imposed tariffs of up to 50 percent on India and has even threatened more. China firmly opposes it. In the face of such acts, silence only emboldens the bully. China will firmly stand with India to uphold the multilateral trading system with the world trade.”

The tariffs issue is expected to figure when President Xi Jinping plays host soon to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit, an event which will see the participation of India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Russia’s President Vladimir Putin.

China taking the side of India over American tariffs is highly unlikely to change the perceptions of President Trump. If anything, it could irritate him more, even as others are pointing to the weak logic, the inconsistencies, and President Putin’s own remark that Russia’s trade with the United States has grown since the time President Trump came to office.

“When the new administration came to power, the bilateral trade started to grow. It’s still very symbolic. Still, we have a growth of 20 percent,” Putin said at a press conference after the Alaska summit, making the point that the United States and Russia had a lot to offer each other in trade, digital, high tech, and space exploration. The flip side to Beijing’s support for India, some sceptics would maintain, is a ploy designed to further stoke the anti-India fires in the White House and among administration hawks.

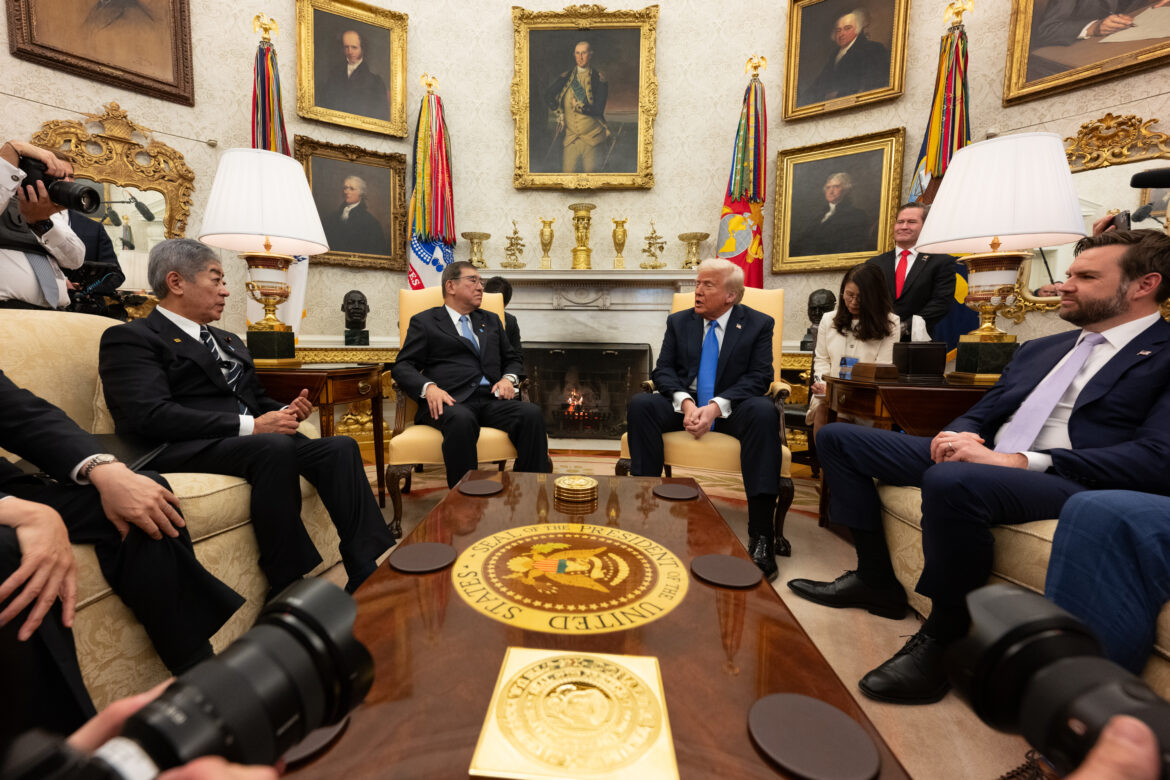

But strong traditional allies of the United States like Japan and South Korea also do not find anything amusing in the goings-on and perceive themselves to be at the receiving end of both trade and defense spending. The tirade unleashed on Europe, that it is over-reliant on America and spends little on collective defense, is also passed on to Seoul and Tokyo, who apparently have quietly started to mull options.

The inconsistencies coming out of Washington are forcing allies to question the long-term commitment of Washington and, in the aftermath of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, to question if the nuclear umbrella would be available in the event of a showdown. In the East Asian context, that would be China over Taiwan and North Korea over South Korea, which will invariably bring in the United States and Japan, as it is the largest overseas base facilitator for the United States.

In all that security-strategic scare in East Asia, the rather difficult “nuclear” option of both Japan and South Korea is surfacing, adding to the discomfort of some in that neighborhood. With its sophisticated defense industry, hi-tech and uranium enrichment capabilities, Japan has for long been seen as being “a screwdriver away” from assembling a nuclear bomb; but South Korea, even with all its developed military hardware, is not seen as having the technology required now for reprocessing.

For the only country to have seen the horrific impacts of the two atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki eighty years ago, the big question for Japan is whether, if push came to shove, it would go the nuclear route.

Disclaimer: The opinions and views expressed in this article/column are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of South Asian Herald.