India’s chronic water crisis has long been a paradox: surrounded by seas yet struggling to provide clean drinking water to millions. Now, scientists at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) claim a potential breakthrough — a siphon-powered desalination system that turns salty seawater into potable water with greater efficiency than traditional solar stills.

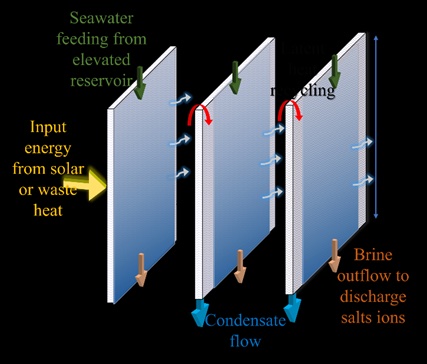

The device, published this week in the journal Desalination, uses a fabric-and-metal siphon to draw water and prevent salt encrustation, a problem that cripples many low-cost purification units. By condensing vapor across a narrow two-millimeter gap, the system yields more than six liters of clean water per square meter per hour — several times what conventional models deliver.

Government officials hailed the development as a step toward “sustainable water independence” for coastal and arid regions. But outside experts are more circumspect.

“Every few years we hear about a revolutionary desalination design,” said a senior researcher at the International Water Management Institute. “Most fail to scale because they either break down in the field, prove too costly for rural use, or lack supply chains for maintenance.”

Indeed, desalination in India has a patchy record. Tamil Nadu’s large reverse osmosis plants supply Chennai with millions of liters daily, but critics say they are energy-hungry, expensive, and discharge brine that damages marine ecosystems. Smaller, solar-powered stills introduced in Gujarat and the Andaman Islands a decade ago fell out of use due to maintenance problems.

The IISc team argues their siphon approach solves two critical bottlenecks — salt buildup and limited water lifting. But whether that translates to reliable performance under monsoon rains, high humidity, and constant exposure to corrosive seawater remains untested.

“Lab efficiency numbers sound impressive,” noted a Mumbai-based water engineer, “but what matters is: can a village panchayat afford it, repair it, and keep it running year after year?”

Affordability is also a looming question. While the system uses inexpensive materials like aluminum sheets and fabric, scaling up production, distribution, and service networks could push costs beyond the reach of the very communities it aims to serve.

Some analysts warn against placing too much faith in technological fixes. “India’s water crisis is not just about scarcity — it’s about mismanagement,” said an activist with a grassroots water rights collective. “We keep looking for gadgets instead of addressing leaking pipelines, over-extraction of groundwater, and inequitable distribution.”

Still, few dismiss the promise of IISc’s work outright. If proven viable in field trials, the siphon system could complement broader water strategies, especially in disaster-hit coastal areas or small island nations where conventional desalination is unfeasible.

For now, the invention represents hope — but also a reminder of how difficult it is to turn elegant laboratory science into lasting solutions for a thirsty nation.