What does it mean to be human? Two unusual exhibits bring us closer to our shadow selves, forcing the viewer to ask hard questions: how do we engage with the world? Do we confront history, or do we accept and move on?

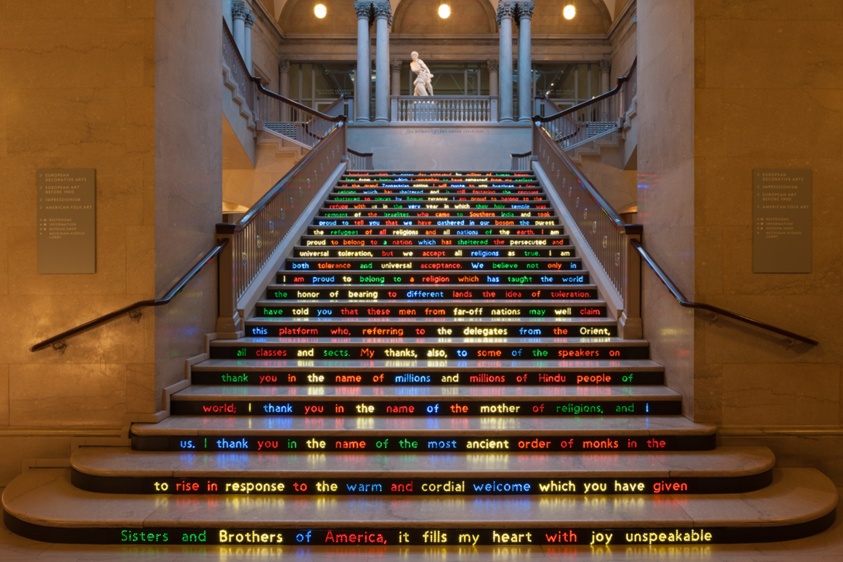

Stepping through the glass doors of the Art Institute, the rush-hour sounds soften, and a few steps take us around the bend to Jitish Kallat’s Public Notice No. 3 – a rendition of Swami Vivekananda’s “Sisters and Brothers of America” speech at the first World Conference of Religions. The words are rendered in LED lights on the risers of the Women’s Board Grand Staircase – the exact spot where the original speech was delivered on September 11, 1893, exactly 108 years before 9/11.

Using the five colors of the U.S. Homeland Security threat advisory system – red for severe risk of terrorist attack, orange for high risk, yellow for elevated risk, blue for general risk, and green for low risk – the work evokes an institutionalized system designed to ensure that people lived their lives in fear.

Like Public Notice No. 1, a rendition of Nehru’s “Tryst with Destiny” speech that involves rubber glue and fire, and Public Notice No. 2, which uses mirrors and resin bones to etch M.K. Gandhi’s speech on the eve of the Dandi March, Public Notice No. 3 continues Kallat’s exploration of how history shapes the present. Through LED illumination, he challenges viewers to believe that there is hope in that history.

Kallat recasts Vivekananda’s 1893 call for tolerance and unity in the visual language of post-9/11 America. The number 108 – marking the years between the two events – became the installation’s geometric foundation, evoking cycles of time and interconnectedness.

As you reach the mezzanine, notice that all four paths to the first floor offer the same message of hope within fear. That sense of being perpetually afraid is accentuated by an effective site-specific adaptation – for no matter which of the four paths you choose to enter or exit the Grand Staircase, you will read the same speech in its entirety by the time you reach the first floor.

Only one of those paths takes you directly to Galleries 141–142, where Raqib Shaw’s Paradise Lost – an epic labor of love – unfolds as a 100-foot, 21-panel interconnected journey through Kashmir’s troubled past and present. Shaw uses remembered motifs from his childhood in the Kashmir Valley – the Khatamband tradition of geometric ceiling patterns in Sufi shrines, pinjrakari latticework on windows and screens – and merges them with years of immersion in the vibrant world of Western art.

This work began in 1999, when Shaw was still a student. Now, more than 30 years later, the epic is still not complete (there’s reportedly another 30 feet still being painted). The proportions tell only part of the story. The opening panel gives the viewer a glimpse of what’s to come: a beast, head thrown back, wearing a crown reminiscent of Miss India, seemingly howling. Yet the viewer’s attention is drawn to the feet – encased in vibrantly colored, bejeweled boots reminiscent of classic Doc Martens. Further along the panels, another beast appears, again crowned but barefoot, its face resembling the Lion King, holding a rhinestone-studded hoop. Look closer and you’ll see a dark gray, tortured djinn emerging from the sky.

In a conversation with the Art Institute’s curator M. Dutta, Shaw discussed his search for materials to translate his imagined images onto canvas. He initially discovered Hammerite – a coating used to cover rust in construction and automotive industries – as a way to move beyond traditional oils. Over time, he settled on using enamel paints from the auto industry, mixed in an old paint machine bought on eBay, to achieve the range of colors for the world he envisions.

Not everyone is a fan. In an article, The Guardian described Shaw’s work as “bonkers” (https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/apr/02/paradise-painted-porcupine-quill-wild-visions-raqib-shaw). A decade ago, The New York Times offered free advice: “Mr. Shaw should work small, avoid shading his colors, and lay off mammals for a while.” Shaw clearly didn’t heed the advice and instead continued along the path that fulfilled him.

The epic canvas fuses Milton’s 17th-century masterpiece with Shaw’s own story of displacement, creating a shimmering allegory of life’s arc – one the artist describes as his journey “from youth to decrepitude and death and beyond.” Paradise Lost is as much a personal story of exile and loss as it is geopolitical. Shaw, as a young teenager and later a young adult, appears throughout the work – close, yet distant. His art is not only dazzling, it bites. It’s the kind of experience worth traveling many miles to see.

Bearing Witness

In an age of increasing division, both Shaw and Kallat remind us that the work of creating a better world – of expanding horizons, of healing from violence – is ongoing. It requires the same patience and precision that Shaw brings to each carefully applied porcupine quill stroke, and the same thoughtful illumination that Kallat brings to forgotten words that urgently need to be remembered.

Art has the unique power to make history at once personal and collective. Kallat and Shaw are bearing witness – for themselves and for those they speak for – recording and interpreting not just what they saw and heard, but how it made them feel then and still does now.

Experiencing these works together, even for a short while – Shaw’s exhibition runs through January 2026, while Kallat’s continues until May 2026 – offers visitors to Chicago’s Art Institute a rare opportunity to engage with art that doesn’t merely decorate or entertain. It helps us process collective trauma and imagine better possibilities.

Disclaimer: The opinions and views expressed in this article/column are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of South Asian Herald.