Most stories live quietly. They are one of many in a kaleidoscope. Mine begins in 1975, with a long flight from India and a decision that changed the course of my family’s life.

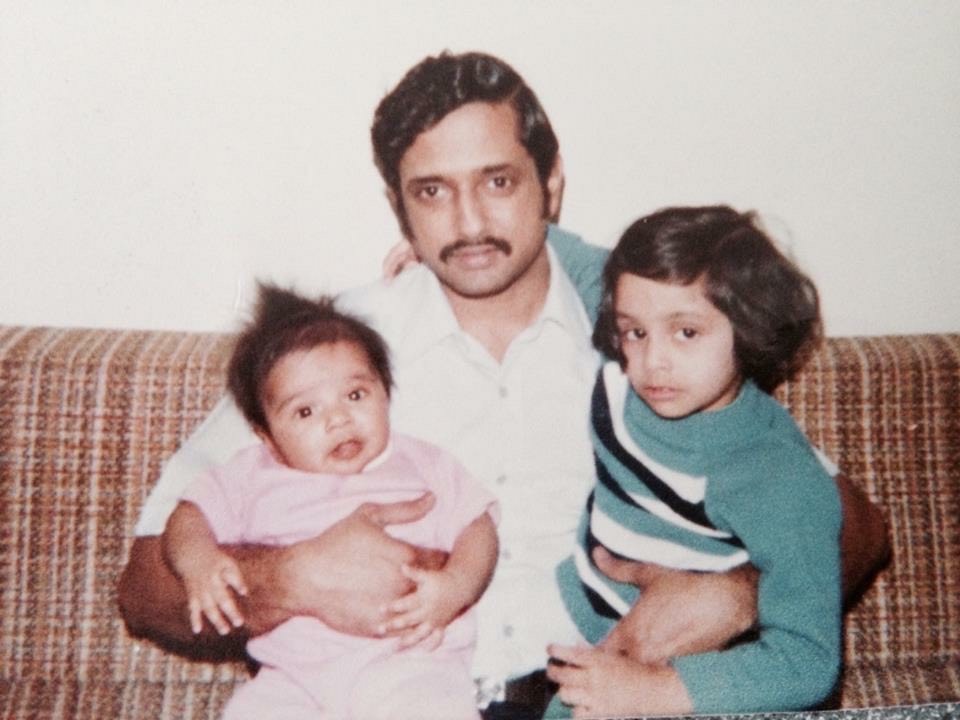

My parents emigrated to the United States as part of a wave of skilled workers the government actively courted. Acquiring green cards was straightforward for certain kinds of professionals. America imagined it needed “top” minds, and my parents imagined something too: opportunity. They packed their degrees, their aspirations, and their two-year-old daughter. My brother would arrive two years later, born in a New Jersey hospital where the nurses tried out his name as if it were a word they’d never seen and weren’t quite sure how to pronounce (possibly true).

For my parents, the choice to move continents was monumental. This was the time of trunk calls and mailing cassette tapes so that my grandfather in Bombay could hear me singing. For me, growing up “American” was something I absorbed before I consciously understood. Childhood teaches assimilation faster than geography or language. I learned English with a Jersey cadence, but I also learned, over time, that parts of my identity felt untethered, floating just beyond reach.

Like many first-generation children, I grew up negotiating the gap between what I knew privately and what I saw publicly. I experienced the taunting of classmates who didn’t know the difference between Indian and Native American, and curricula in which immigrant history meant Ellis Island and not much else. Textbooks treated America as if it were built through orderly waves rather than overlapping migrations, enslavement, exclusions, and reinventions.

A culture that did not yet know what to do with a name like mine. There is a reason I cried when I heard then-Senator Barack Obama’s famous words recounting “The hope of immigrants setting out for distant shores … The hope of a skinny kid with a funny name who believes that America has a place for him, too.”

I did not know, as I studied “American” history, that South Asians had been in North America for more than a century.

School never taught me about the Sikh lumber workers of the Pacific Northwest in the early 1900s, the Bengali and Punjabi sailors who jumped ship and made new homes, or the students and activists who organized decades before the model minority stereotype existed. For years, I assumed our presence in this country was recent, narrow, and solitary.

Then I encountered the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA), and my eyes were opened.

SAADA’s digital archive isn’t just a collection of items; it’s a vital space where community identity and belonging are cultivated and reinforced.

Inside SAADA’s digital archive are photographs, letters, menus, poems, petitions, zines, newspapers, marriage certificates, and passports, worn down from decades of handling. SAADA documents activists, restaurant owners, scholars, laborers, families in their wedding clothes, and individuals crossing oceans, all reflecting the diverse stories that shape community identity.

These are not simply artifacts. They are mirrors. When a community sees itself reflected, not distorted, not reduced, not treated as an afterthought, its understanding of itself changes.

Identity becomes anchored, not provisional. Belonging becomes intergenerational, not conditional.

As someone who has spent my career in philanthropy and nonprofit leadership, I understood immediately how vital but fragile this work was. I was honored to be asked to join SAADA’s Board. After my term ended, I have endeavored to stay close. Some responsibilities (opportunities, really) outlast titles.

The seismic shifts in the nonprofit sector this past year made that commitment feel even sharper.

Five of SAADA’s federal grants, totaling more than $1.5 million, were terminated overnight. The explanation was bureaucratic and blunt: the grants “no longer met the needs of the federal government.”

To many organizations, that kind of loss would dictate compromise or retreat. SAADA chose neither. Instead of scaling back, SAADA expanded its work: more lesson plans, more public programming, more archival access, more community history made visible.

SAADA’s message is clear. Political vagaries and misdirection will not hamper the work of preserving history.

People might wonder why the sustainability of an archive matters when so many of today’s crises feel so immediate.

The answer is simple: history shapes belonging.

When a young South Asian American sees evidence of their community in 1910, 1950, 1983, or 2001, something internal shifts. They stop viewing themselves as perpetual visitors. They inherit continuity rather than longing for it. Belonging isn’t sentiment. It’s basic infrastructure for cultural, civic, and psychological alignment.

Belonging influences who participates fully in democracy. Who speaks up. Who feels entitled to dignity, representation, and safety.

It answers a question many of us grew up carrying silently: Do we have the right to be here?

The archive responds: We always did. We always will.

Today, I get to watch my daughter and son (both Boston-born… Go Sox!) grow up with stories and a sense of history that I never had access to. Not because the past changed, but because someone finally preserved it.

When I think about SAADA, I think about that continuity with gratitude. I remember toddler-me being carried off a plane in 1975, the generations who came before, and the endless generations who will come after, never doubting that they belong in the American story.

That is what an archive does at its best: it gives a community back to itself. Once you have been returned to history, you cannot be erased from it.

As you and your families discuss your year-end giving, I ask that you consider the role of community memory not as a luxury, but as a safeguard. Take a moment to reflect on your part of the American story, then take meaningful action.

To learn more about SAADA’s work or to make a contribution, visit www.saada.org. The history of the South Asian diaspora cannot protect itself. But we, the people, can.

Disclaimer: The opinions and views expressed in this article/column are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of South Asian Herald.

![2025-04-12 [Family Photo 8] Board Game Extravaganza[2]](https://southasianherald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/2025-04-12-Family-Photo-8-Board-Game-Extravaganza2-1170x878.jpeg)