A decade-long push for financial inclusion in South Asia has produced impressive numbers on paper. According to the World Bank’s Global Findex Database 2021, nearly 7 in 10 adults in the region now hold a formal financial account—more than double the figure in 2011. India alone accounts for the lion’s share of this progress, having added hundreds of millions of account holders through state-backed schemes like Jan Dhan Yojana.

But scratch beneath the surface, and the picture is more nuanced. Critics argue that the region’s financial inclusion story is at risk of being reduced to a “bank account-counting” exercise, with limited attention to usage, impact, or sustainability.

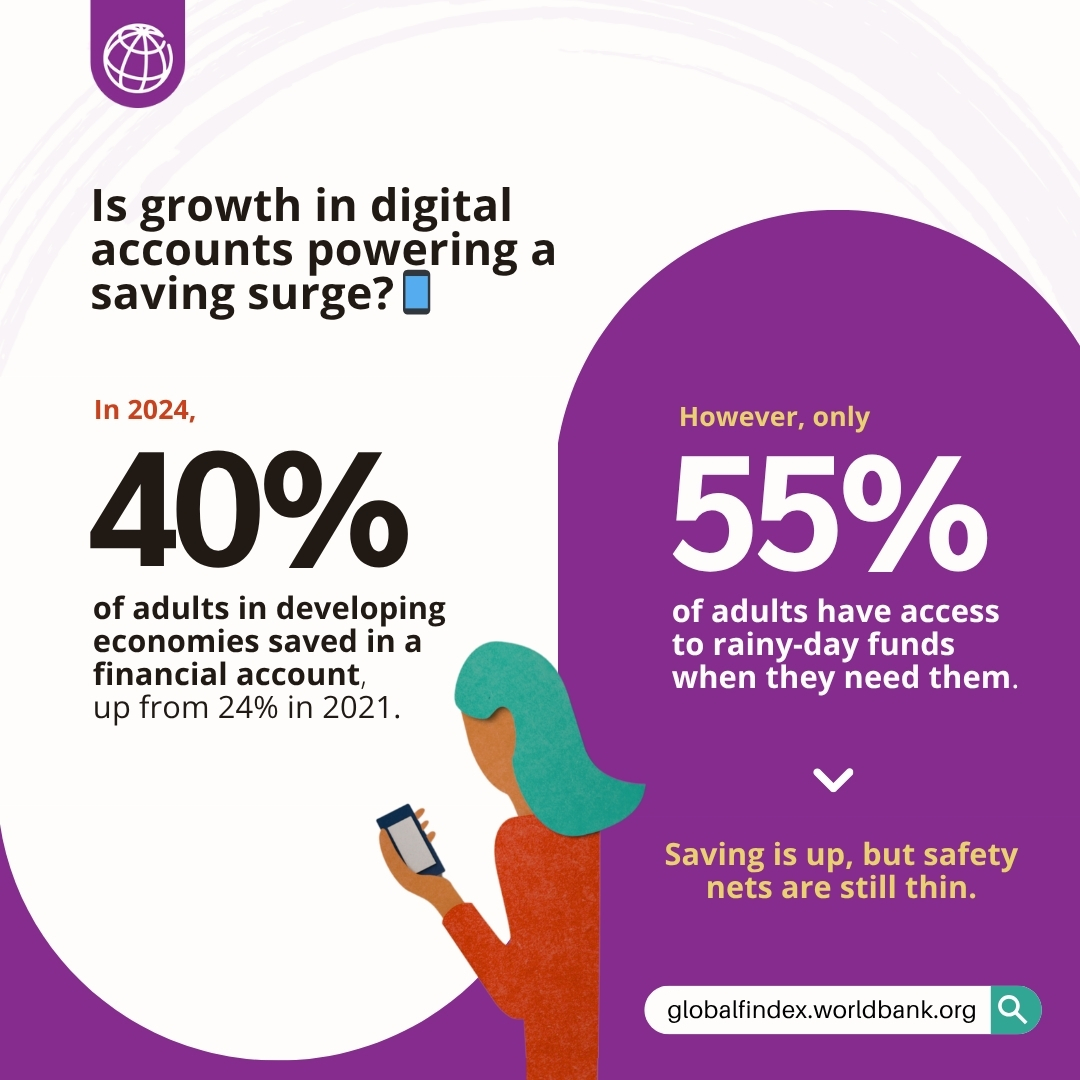

The Digital Surge—and Its Discontents

The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed a dramatic shift toward digital payments. India, for instance, saw over 80 million adults make their first digital merchant payment during the pandemic. Mobile apps, UPI, and QR codes became part of everyday transactions in urban India, while governments across the region rushed to deliver cash transfers via bank accounts and mobile wallets.

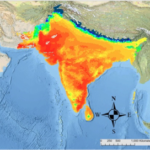

Yet this digital transformation has left large sections of the population behind. In Pakistan, only 21% of adults owned a financial account in 2021. In Bangladesh, women and rural residents continue to report low levels of access and awareness. Across South Asia, women remain at a disadvantage: the gender gap in account ownership, though shrinking, still stood at 13 percentage points in 2021.

Even in India, where inclusion metrics have surged, meaningful usage lags. The report reveals that one in three Indian account holders did not use their accounts in the past year—raising questions about whether these accounts are improving lives or simply ticking boxes on administrative dashboards.

“Ownership is only the first step,” said a regional policy advisor working with financial regulators. “True financial inclusion means trust, usability, and protection—areas where South Asia continues to underperform.”

A Tale of Two Realities

South Asia’s digital finance boom has been hailed as a global success story. Biometric ID systems like Aadhaar in India have enabled mass account openings. Mobile penetration has improved. Governments have streamlined welfare delivery.

But this celebratory narrative obscures systemic blind spots. Over half of unbanked adults in South Asia already own a mobile phone yet fail to use it for financial transactions—often due to lack of digital literacy, poor user experience, or concerns about fraud. In rural Pakistan and Nepal, women’s access to mobile phones is not only limited but socially restricted.

The implications go beyond access. Among those who do receive wages or benefits digitally, one in five in developing economies reported paying unexpected or high fees. In countries with weaker consumer protections, digital accounts have introduced new vulnerabilities.

“Digital doesn’t always mean equitable,” noted a fintech researcher in Dhaka. “We’re seeing elite capture of financial technologies—urban, male, and literate populations benefit disproportionately.”

Government Role: Enabler or Bystander?

Public policy has played a dual role—sometimes a facilitator, often a limiter. India’s direct benefit transfer (DBT) model is cited as a global best practice. But in countries like Bangladesh and Pakistan, the absence of interoperable ID systems or fragmented regulatory frameworks has slowed progress.

The World Bank warns that policy support must go beyond infrastructure. Without digital literacy campaigns, grievance redress systems, and tailored financial products, millions risk being excluded from the very systems meant to empower them.

There is also a cautionary note on account dormancy—especially in economies where accounts were opened primarily to receive one-off government transfers. “You can’t digitize poverty out of existence,” said a development economist in Colombo. “Digital accounts need to be backed by income opportunities, safety nets, and trust.”

The Road Ahead: Inclusion Redefined

As South Asia rides the digital finance wave, the challenge is no longer one of reach—but of relevance. Policymakers will need to shift from scale to substance. That means bridging the gender gap not just in account ownership but in mobile access. It means making financial products intuitive, affordable, and responsive to real-world needs.

The Findex report offers hope—and a warning. The region has come far in a decade. But unless digital finance ecosystems are reimagined with equity at the center, South Asia risks entrenching a new kind of exclusion: one that hides behind an interface.