Before school drop-offs. After the children are asleep. Between paid work, care work, and the invisible labor of holding families and communities together. During motherhood, that is exactly what entrepreneurship looked like in my own life. But before being a mother, my time was my own. I built my first business at 20, in London.

It was modest by any standard: a small tax refund service helping people reclaim money they were owed. But to me, it felt electric. I was young, single, and living in the city of London that hummed with ambition. I could work late into the night without consequence. No one needed me to pack lunches, book doctor’s appointments, or remember which day was PE kit day. My time belonged to me. That freedom rarely appears in economic data, but it sits quietly behind it. It is the unspoken advantage that shapes who gets to take risks, who gets to stay late, and who can afford to fail once or twice before succeeding.

Ten years later, I started my second business: a strategic communications and PR firm. This time, I was 30, married, and the mother of a one-year-old. On paper, I was far better equipped. I had experience, networks, clarity, and a deeply supportive husband who genuinely shared the load at home. In reality, it was one of the hardest things I have ever done.

The business was built in fragments of time: between feeds and fevers, during nap windows, and at 3am while rewriting proposals on too little sleep. The ambition was the same. The energy was not. Life had become beautifully, impossibly complicated. And if it was that hard for me, with privilege, education and support, what does entrepreneurship look like for millions of other women, carrying most of the cooking, cleaning, childcare and emotional labor alongside the need to earn?

The Economy’s Best-Kept Secret

Around the world, women do roughly twice as many hours of unpaid care work as men. Cooking, cleaning, childcare, elder care, emotional support: the work that keeps households and societies functioning. Globally, according to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), an estimated 708 million women are outside the labor force primarily because of unpaid care responsibilities.

For men, the equivalent figure is around 40 million. This unpaid labor is the dark matter of the economy: unseen, uncounted, but shaping everything. It also explains something that policymakers and investors often miss. Starting a business is greedy. It wants your time, focus, courage and stamina. When a man starts a company, there is a good chance someone else is cooking dinner. When a woman starts a company, there is a good chance she is still the one cooking dinner, checking homework, and coordinating care for ageing parents. In South Asia, that imbalance is sharpened by culture and by policy. Fewer than one in five businesses in the region are owned by women.

Around 70 per cent of women-owned small and medium enterprises are underserved or entirely excluded from formal finance. In Sri Lanka, only about a quarter of SME owners are women, and fewer than 3 per cent of the workforce are entrepreneurs at all. Globally, the figure is closer to 10 per cent. This is not because women are less capable. It is because they are more tired.

Learning Leadership Without Calling It That

My belief that building a business was “normal” did not come from glossy success stories or motivational slogans. It came from watching women work. In Pakistan, my mother and aunts ran a school. It did not look like entrepreneurship in the way business magazines define it. There were classrooms instead of corner offices, chalkboards instead of pitch decks.

But the fundamentals were all there: managing cash flow, paying staff, complying with regulations, earning community trust. Later, growing up in the UK, the most visible figures of authority were women. Margaret Thatcher was Prime Minister. The Queen was head of state. When women occupy the frame of power, leadership stops looking like a male exception. That is not the case everywhere. Many girls grow up without seeing women in visible business or political leadership. And research consistently shows that role models matter. When women see other women lead, they are more likely to start businesses, put themselves forward, and stay the course when things get difficult.

Confidence, Capital and the Oxford Classroom

For several years, I taught entrepreneurship at the University of Oxford’s business school, including on a technology accelerator designed for women. It was one of the most revealing experiences of my career.

On paper, the men and women in those classrooms were evenly matched. Similar qualifications. Similar professional experience. Similar intelligence and work ethic. What differed was confidence. In pitch sessions, men were more comfortable projecting big futures and big numbers. Women often arrived better prepared, with more evidence and realism, but spoke more cautiously about scale.

Over time, that confidence gap translated into a funding gap. And that funding gap became a growth gap. The data is stark. In 2023, startups founded solely by women received around 2 per cent of global venture capital funding. This is not because women build weaker businesses. In fact, multiple studies show that women-led startups often generate higher revenues per dollar invested and operate with greater capital efficiency. Equal capability is meeting unequal capital.

Bias, Risk and the Cost of Care

The funding gap is often explained away as a pipeline problem: not enough women pitching, not enough “investable” ideas. The reality is more uncomfortable. Investors, like all humans, carry bias. They tend to see leadership potential in people who resemble their mental image of a founder, which still defaults to male. Research shows men are more likely to be asked questions about growth and upside, while women are more often questioned about risk and downside.

Those differences directly affect how much money founders raise. Layer unpaid care responsibilities on top of this, and the picture sharpens further. A woman often enters a pitch having already worked a full shift at home. Her risk tolerance is shaped by school fees, dependent parents, and the knowledge that she has less margin for error. This is not a lack of ambition. It is a different calculation. When women do reach visible leadership, they face harsher scrutiny.

Leadership research has long shown that women are penalized for not fitting traditional stereotypes: criticized for being too soft or too strong, too emotional or too cold. In entrepreneurship, that scrutiny has real costs. It can dampen visibility, slow decision-making, and erode confidence at precisely the stage when speed matters most. Women are not leading from weakness. They are leading with a heavier backpack.

A Quiet Shift in the Odds

And yet, there is genuine cause for optimism. Technology is quietly reshaping what entrepreneurship looks like, particularly in knowledge-based and professional services. AI tools now handle tasks that once consumed hours: first drafts of proposals, data analysis, document summaries, marketing copy. Video calls have normalized remote pitching and client work in ways that were unimaginable a decade ago.

For women balancing care and ambition, this matters enormously. It does not remove the care burden. But it allows the remaining hours to be used more efficiently and, crucially, on their own terms. A consultancy, design studio or advisory business can now be built from a laptop, from a kitchen table, between school runs. The friction of constant physical presence and performative long hours is slowly eroding. This shift is not loud. But it is profound.

Why South Asia Cannot Afford to Wait

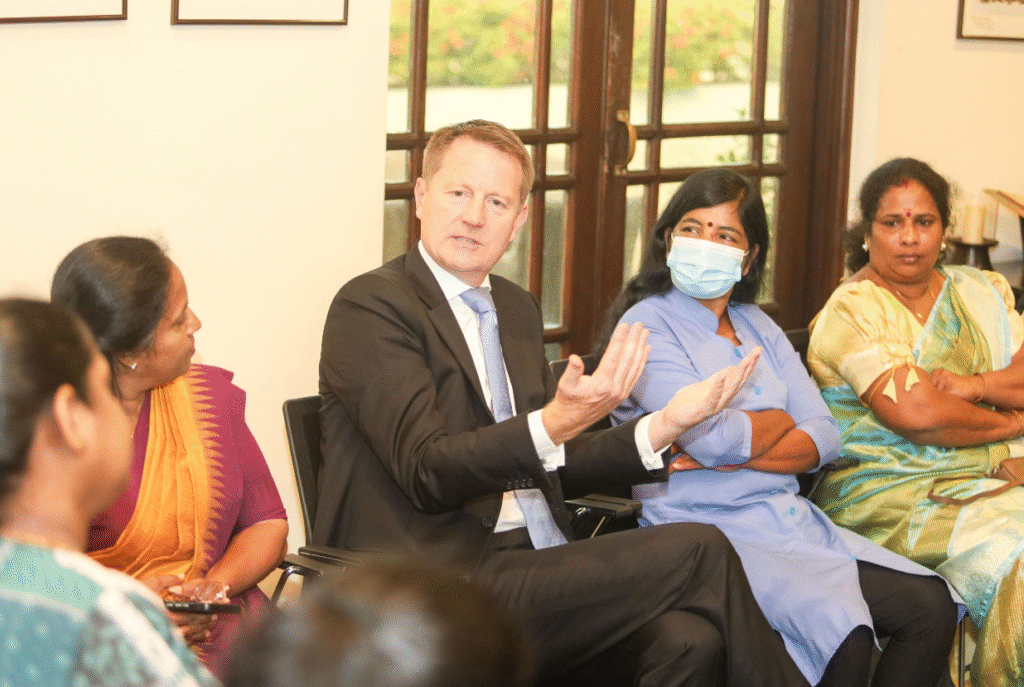

Which brings us back to South Asia, and to the women building businesses across the region, often with far fewer resources than their peers in London or Oxford, but with the same drive. When initiatives such as HSBC and Sarvodaya’s Women Empowerment and Digital Inclusion program in Sri Lanka, delivered through Sarvodaya Fusion commit funding, training, and mentorship to women entrepreneurs, this is not charity. It is economic strategy.

Global evidence is clear: investing in women’s entrepreneurship drives inclusive growth, reduces poverty, and builds resilience. Women are more likely to reinvest earnings into education, health and community infrastructure, multiplying the impact of every rupee. But if these efforts are to move beyond pilot projects, they must be matched by deeper shifts. Recognizing unpaid care as economic work. Closing funding gaps with intentional capital. Telling different stories about what an entrepreneur looks like.

Because when a woman who has cooked dinner, bathed a child, soothed a parent and still finds the energy to write a business proposal sits down at her kitchen table, she is not just starting a “side hustle,” she is quietly renegotiating the status quo.

Disclaimer: The opinions and views expressed in this article/column are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of South Asian Herald.