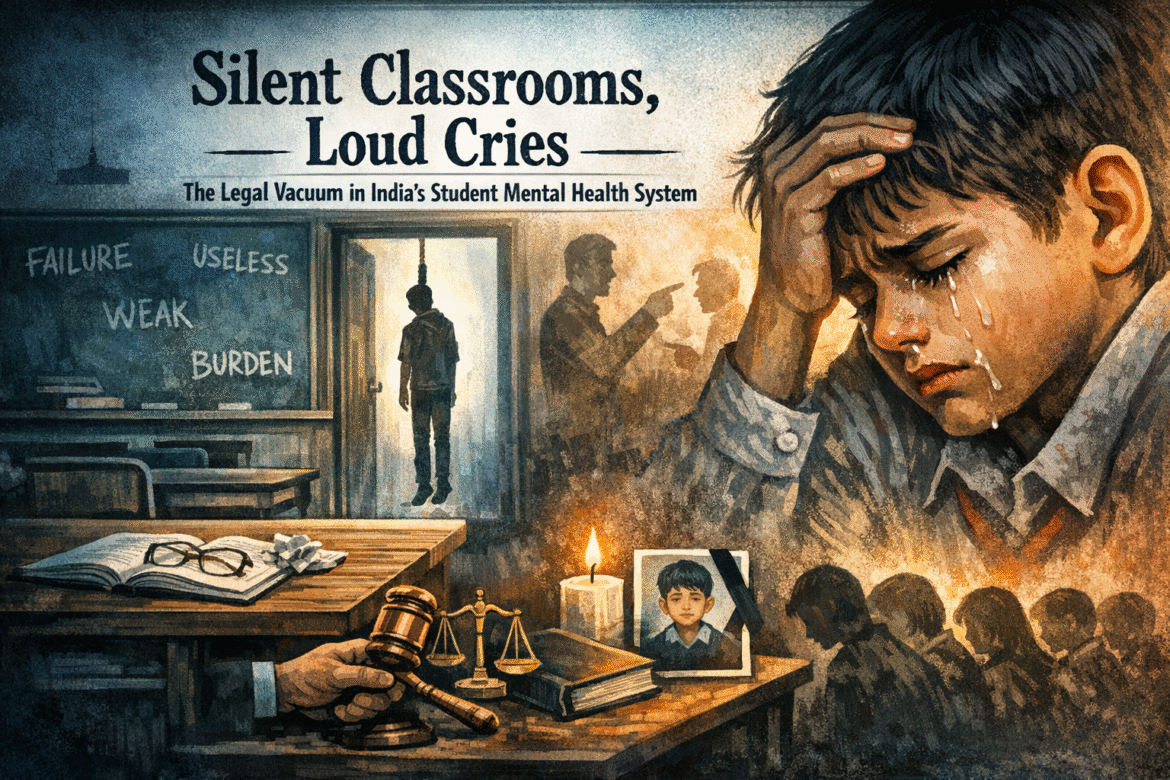

A class 10th student of St. Columbia school, grappling with struggles of school and concomitant harassment, decided to give up his life. The sad part is that he reached out to the school counselor, his teachers, and even his family, yet help never came in time, and a young life rich with dreams and ambitions was tragically cut short.

In the last decade, student suicide rates rose 65 per cent, an abhorrent figure that the legal system is failing to recognize, and young, bright lives keep on being taken. It was also found out that the student was vehemently disparaged by the teachers, and was cited as a bad example as an underperforming student. The tragedy is not only personal but institutional when teachers meant to guide and protect become subjects of fear and humiliation, it exposes a deeper state of lack in training, sensitivity and academic accountability.

The article seeks to delve into the legal lacuna that exists within the mental health framework in India and the implementation problem that it faces. Subsequently, it also lays down the tragic state of the Indian education system and its precarious impact on student mental health. Further, it lays down the psychological inspirations the Indian mental health framework can take from other countries by doing a comparative analysis. The article aims to address the suicide cauldron, and the mental health calamity India is going through, and subsequently, how law and better implementation could effectively help to address the specific issue. The article concludes that with timely support, misfortunes like Shourya Patil’s could have been prevented, saving innumerable young lives.

SYSTEMATIC FAILURE OF MENTAL HEALTH CARE IN INDIA

According to NCRB data, children are disconsolately swamped with academic pressure, familial expectation and social scourge. The UNICEF Report on the state of world children claims that one in seven young people between the ages of 15 and 24 in India experience poor mental health; however, only 41 per cent felt the need to actually seek help.

While the Indian legal system by enacting the Mental health care act 2017 has attempted to ensure that the mental health law is progressive by bringing on patient rights, decriminalizing attempts to suicide, but implementation funding and weak implementation propel such efforts rudderless. The CBSE, through the new education policy have commanded to pursue steps in positive directions but deplorably failed seeing the actual gap that persists in the lack of professional clinical psychologists in Indian schools.

India is perceived as a counselling deficit sector where over 93 per cent of schools don’t have a professional counsellor on the board, leading their agonizing concerns unattended for years. The lack of trained counsellors often leaves students’ talents unrecognized, leading them to unsuitable career choices and unrealized potential. A Mindler Report on Career Option awareness among Indian students revealed that 93 per cent of students aged 14 to 21 were informed of only seven career options, though there are more than 259 different types of job options available in India.

The National Mental Health Survey of India 2015-2016 further illuminates that every sixth Indian needs mental health care. The current level of treatment utilization and large treatment gap among all disorders is a cause of concern. There is a major cause of concern for the relative failure to educate the population and decrease stigma, and empower the primary health care personnel, at the earliest stage of the development of a child. Extensive research showcases that early identification and intervention in childhood and adolescence significantly improve long-term well-being. Children who receive better, timely mental health care and development support are seen to perform better in their adult lives. The early recognition and treatment of mental health issues help prevent the illness not to becoming severe in the near future or leading to a comorbid illness. Public health reporting in India notes that there is a lack of early mental health support in India, which increases the risk of mental disorders later in life.

THE PEDAGOGICAL DUTY OF CARE

Teachers could play an imperative role in identifying and then further addressing the mental health issues at an earlier stage of life. The Cambridge University Study showcases that integration of mental health education among adolescents leads to improved outcomes. The pupils developed significantly more empathy, reduced stigma towards peers with mental health difficulties and showed improvements in conduct and prosocial behaviors. Section 75 and Section 82 of the Juvenile Justice Act further elucidate that corporal punishment to discipline a child is punishable and could attract a fine of up to rupees 5 lakhs and imprisonment of up to 5 years. Yet, cases of teachers punishing and mocking students, in the name of discipline, are quite normalized in the Indian education system, and such incidents are overlooked by both the school administration and the parents until the child reaches a point of no return.

Section 17 of The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009, prohibits physical punishment and mental harassment of students in schools, and violation can attract disciplinary action against the teacher. In the case of Parents’ Forum for Meaningful Education v. Union of India, the court condemned corporal punishment in schools, held it incompatible with the child’s right to life and dignity and further imposed on the state the immutable responsibility to protect children from corporal punishment.

In the case of Kishore Guleria v Director of Education, the court reinstated that corporal punishment has no place in India and is subsequently inconsistent with India’s obligation under the International Convention on the Rights of the Child. In the recent judgment of Sukhdeb Saha vs State of Andhra Pradesh student’s mental health was declared as an integral component of the fundamental right to life under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. Teachers are the first responders, and most teachers in India lack mental health training. Consistent mental health education for teachers is crucial to meet the rising student mental health needs. As seen in cases like Shourya Patil’s, untrained hands meant to guide become the very weight that breaks a child’s spirit.

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS: LEARNING FROM GLOBAL SUICIDE PREVENTION MODELS

In many countries, the mental healthcare structure in schools is unequivocally strong, leading to lower suicide rates and thus performing better in the world happiness index. The best practices in happier countries in Europe with low suicide rates include a mental health-friendly environment, building resilience, such as Ice Hearts, This Is Me, and Zippy Friends. For example, the Iceheart is a Finnish prevention program that uses team sports to provide long-term mentoring support to socially vulnerable children and adolescents. Many countries, like Austria, have implemented specific suicide prevention programmes in schools, recognizing individuals with mental distress and then effectively able to prevent suicide by providing adequate mental healthcare at the right time.

In Slovenia, This Is Me is a national youth mental health and wellbeing program aimed at developing social and emotional skills and self-image in adolescents. The programs consist of two universal prevention interventions. Intervention 1 offers anonymous, simple, rapid, free access to online expert advice answering youths’ questions. Intervention 2 consists of a comprehensive model of 10 preventive workshops that systematically address the development of social and emotional competencies and realistic self-evaluation.

Intervention 2 targets school classes in primary/lower secondary education and is implemented mostly by teachers or school counsellors trained for that purpose. India can meticulously learn from the “this is me” program by introducing anonymous digital counselling for students and structured social-emotional learning workshops in schools. Training teachers to lead mental health sessions and normalizing help–seeking in classrooms can build resilience and reduce the risk of suicide at an early age.

The SEYLE study, a broad European randomized trial on the multifarious suicide prevention strategies adopted, showcases that the Youth of mental health probative was found most promising. YAM is a Swedish-developed program that makes adolescents emotionally aware, practically equipped, and not shackled from seeking help. The study found that the program reduces suicide attempts and suicidal ideation after 12 months.

Thus, there exists strong evidence that if implemented correctly student student-focused mental health education can meaningfully lower suicidal ideation in students. Such program implementation is not difficult if accompanied by a strong will. A strong government commitment and a veritable concern for exuberant young lives, thus making the gallery of becoming a space of safety where no student feels invisible and where no one is ever driven to make the irreversible, devastating decision to end their own life.

THE WAY AHEAD: ENDING THE SILENCE AROUND STUDENT MENTAL HEALTH

Suicide is a preventable problem; deaths occurring due to mental breakdown represent the government’s failure to implement effective policies and to belittle the importance mental health should be provided at the foundational level. It’s more daunting that the future of this nation continues to be lost to its inner struggles, representing the glaring obliviousness of the government to countering and drafting policy that might address the devastating problem. While the government has attempted to take certain measures in the right direction with the implementation of schemes such as the Happiness curriculum in the state of Delhi, or by introducing mental health guidelines for preventive, remedial and supportive frameworks for mental health protection and prevention of suicides by students across all educational institutions. However, these measures either lack effective implementation or are inadequate.

In the case of Sukdeb Saha v State of Andhra Pradesh, the Supreme Court directed that all educational institutions must have a uniform mental health policy, which shall be made publicly accessible on the institutional website. Despite this, the majority of Indian schools still lack a “mental health policy,” and mental health is often considered as superfluous by the administration until a tragic step is taken by some. The court also stated that all the teaching and non-teaching staff must undergo mandatory training at least twice a year, meaning that they must be responsibly trained in a beneficial manner to children’s health. However, the lack of such training is evident as corporal punishment is deeply entrenched in the Indian education system, a study claiming that 80 per cent of those in government schools have been beaten by their teachers in the past.

It has also been seen that B.Ed. programs, which are professional degrees that train a person to become a school teacher, share limited servility to psychological classroom methods. The biggest challenge among teachers is a lack of awareness and knowledge about human development theories that are required to proactively resolve mental health issues. The teacher needs to be trained as well as how they treat their students and how to identify early mental health challenges, and how to address them at the earliest stage.

Regular government workshops and adopting internationally propitious programs such as This Is Me and Iceheart could prove beneficial in the identification and resolution of a child’s mental health issue. And having a trained clinical psychologist in every institution is the need of the hour. The lives that have been lost cannot be undone, but decisive action today can protect countless others tomorrow, ensuring that no one is left so hopeless as to mistake a moment of despair for an end.

Disclaimer: The opinions and views expressed in this article/column are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of South Asian Herald.