India and Russia may have showcased a sweeping vision to lift bilateral trade to $100 billion by 2030 at the Modi–Putin summit on Friday, but the optimism of the joint statement jars with the stubborn reality that India cannot significantly expand exports until both sides rebuild a payment system that functions without friction.

The communiqué repeated familiar aspirations about “balanced” trade and “expanded market access,” yet exporters say the real issue is neither access nor demand — it’s whether money actually moves. As one trade executive remarked, the bottleneck today is not tariffs, but the simple question of whether a payment clears without disappearing into weeks of banking limbo.

The numbers capture the imbalance with uncomfortable clarity. India–Russia trade is nearing $70 billion, but almost all of it flows in one direction. Indian exports remain stuck at $4.9 billion, effectively flat despite Moscow’s repeated promises to buy more. Imports, fueled largely by discounted crude, have soared to $63.8 billion.

Oil alone accounted for $50.3 billion, turning the relationship into a single-commodity channel rather than a broad-based commercial partnership. India’s share of Russia’s $202.6-billion import market is a wafer-thin 2.4%, remarkably low for a country that counts itself among the world’s major exporters of pharmaceuticals, textiles, processed food and engineering goods.

A new study by the Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI), released on December 5 during the summit, sets out both the scale of opportunity and the structural flaw that undermines it. The report estimates that Indian merchandise exports to Russia could rise seven-fold to $35 billion by 2030 if India taps product segments where Russia is a major buyer and India a globally competitive supplier. But the study is equally blunt that none of this is feasible without a predictable settlement architecture. As it puts it, “Without a modern rupee-rouble settlement system, Russia may remain India’s biggest oil supplier—but not a serious export market.”

The extent of India’s under-performance spans almost every category. Russia imported $13 billion of food products in 2024, yet India’s combined exports of fruits, oils, meat and dairy failed to cross $250 million. In fruits and nuts, Russia bought $4.34 billion, while India supplied just $38.8 million. Even in meat — a segment where India is a $3.95-billion global exporter — sales to Russia were just $36.5 million. In processed fruits and vegetables, Russia imported $1.15 billion; India sold only $42.7 million.

High-value sectors tell the same story. Russia’s $11.8-billion pharmaceutical market saw India capture barely $413.5 million despite its formidable global footprint. In textiles, Russia imported $3.65 billion of knitwear and $3.03 billion of woven garments; India managed around $100 million in total. Engineering goods show an even starker gap — Russia bought $37 billion worth of machinery and $20.5 billion of electrical equipment, but India supplied just $1.1 billion and $424 million respectively. Consumer goods are the most lopsided: Russia imported $29 billion of vehicles versus $45 million from India; $2.3 billion of furniture versus less than $4 million; and $1.9 billion of toys and sporting goods versus India’s $6 million.

What links these disparate gaps is not the absence of Russian demand or Indian capacity, but the sheer difficulty of concluding financial transactions. Western sanctions continue to distort Russia’s banking links, leaving Indian banks cautious and driving exporters toward circuitous third-country payment routes. Compliance checks create unpredictable delays; remittances often hang for weeks; and even with firm orders, settlement uncertainties deter regular, large-volume business. For many exporters, the risk-reward equation simply doesn’t add up.

The joint statement tries to address this head-on. It says both countries “have agreed to continue jointly developing systems of bilateral settlements through use of the national currencies” and to pursue interoperability between payment platforms, financial messaging systems, and central-bank digital currency frameworks. But until that promise translates into a dependable mechanism, exporters say the commercial potential will remain largely theoretical.

The Federation of Indian Export Organizations (FIEO) responded enthusiastically to the summit outcomes, calling the joint statement “a major step forward” in strengthening trade, economic and connectivity partnerships. FIEO president S.C. Ralhan said the roadmap — including the push for balanced trade, improved logistics, smoother payments and stronger insurance frameworks — aligns closely with the bottlenecks exporters have been flagging for years. He welcomed the reaffirmed $100-billion target for 2030, noting that addressing tariff barriers, settlement frictions and logistics constraints will be central to expanding India’s export basket.

Ralhan also highlighted opportunities in engineering goods, pharmaceuticals, agro-products, textiles, gems and jewelry and tech-driven sectors. He pointed to rising Russian demand for online consumer goods as a promising frontier for Indian e-commerce exporters in categories like lifestyle, home décor and value-added food. He praised the commitment to build reliable payment systems using national currencies and interoperable digital platforms, calling it “a transformative step toward stabilizing India–Russia trade flows.”

The Federation also welcomed sustained cooperation in energy — from oil and gas to petrochemicals and nuclear projects — and the broader connectivity agenda, including the International North–South Transport Corridor, the Chennai–Vladivostok maritime link and the Northern Sea Route. These corridors, Ralhan said, will cut logistics costs and open new gateways for Indian goods. The Russian Far East and Arctic, with opportunities in agriculture, minerals, manpower and pharmaceuticals, also remain on FIEO’s radar.

But the broader truth remains unchanged. Political intent and institutional enthusiasm cannot mask the fragility of the financial plumbing that underpins this relationship. Until India and Russia create a modern settlement ecosystem that is sanction-proof, bankable and predictable, exports will remain a fraction of their potential. For now, the commercial bridge between the two countries rests on a single sturdy pillar — Russian oil — while the rest of India’s export basket waits on the sidelines for a payment system it can trust.

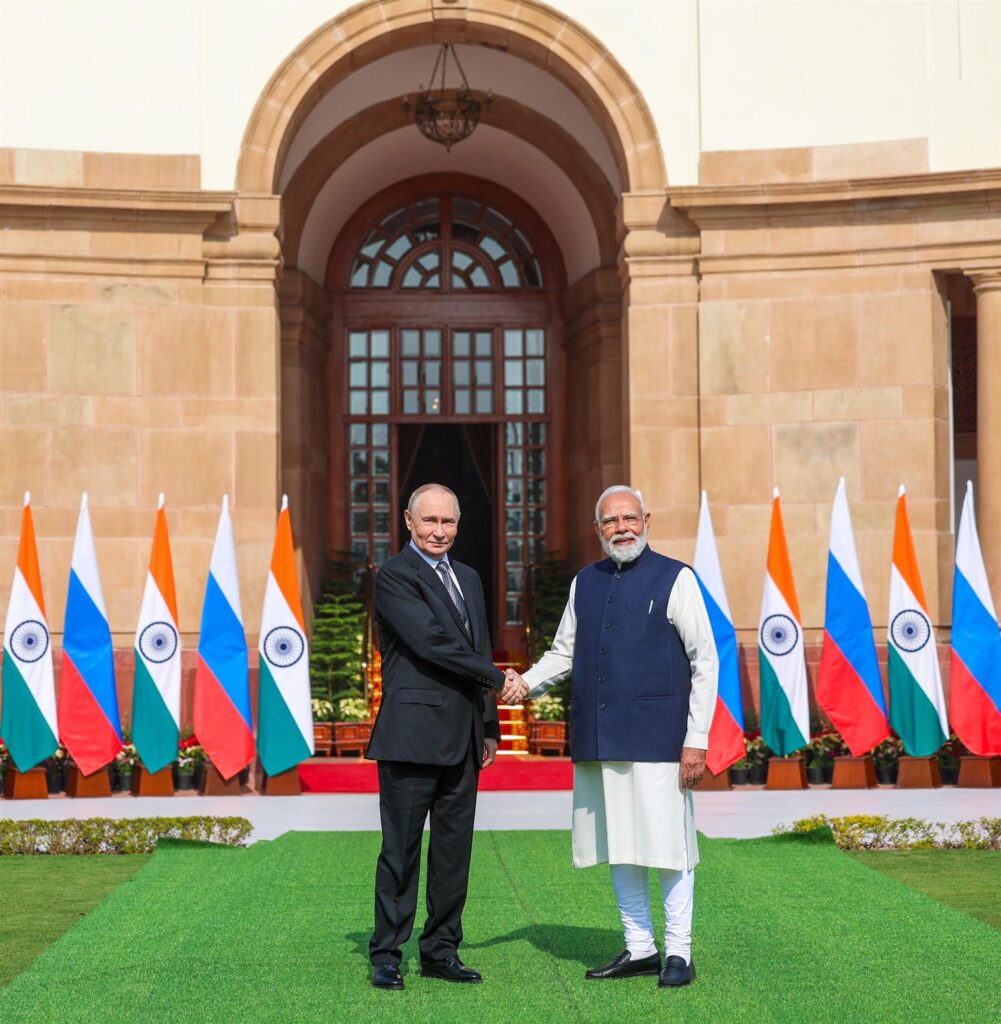

![modi-putin-2-pib[1].jpg](https://southasianherald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/modi-putin-2-pib1.jpg-1170x746.jpeg)