She moved through cinema like something feral that had wandered onto a film set by mistake—too unguarded, too physical, too present for the carefully constructed fantasies of 1950s European film. Brigitte Bardot didn’t perform desire. She exhaled it. And for two incandescent decades, the world held its breath.

What made Bardot dangerous wasn’t nudity or scandal—Hollywood had trafficked in both since its inception. What unsettled audiences, what made censors reach for their scissors and moralists for their pens, was her fundamental indifference to their judgment. She embodied a sexuality that asked for nothing: not approval, not protection, not even love in its conventional sense. She simply was, with a completeness that seemed almost pre-civilizational.

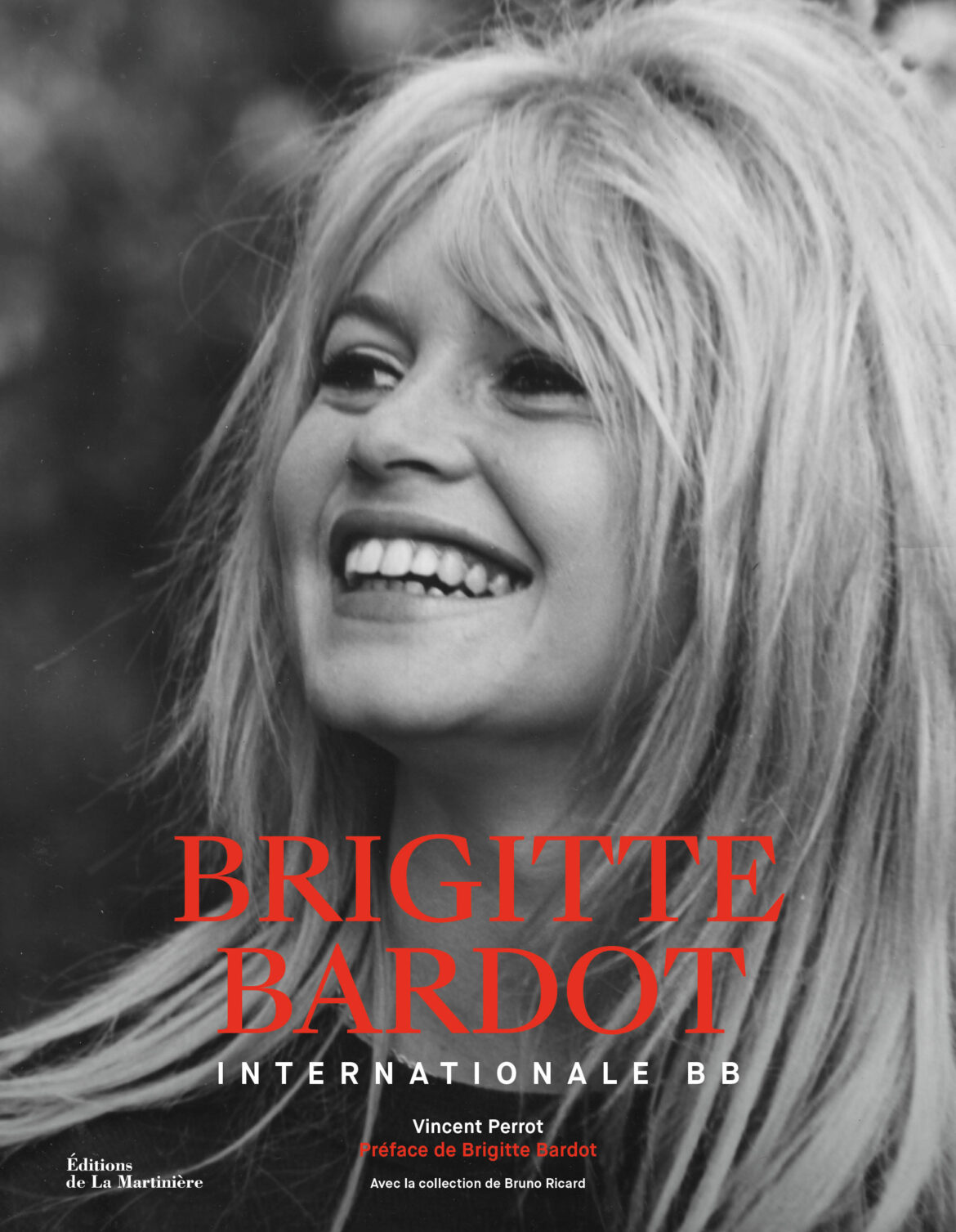

Watch her in those early films—the tousled blonde hair catching Mediterranean light, the pout that suggested boredom rather than flirtation, the bare feet and careless clothes. This wasn’t the polished eroticism of Hollywood starlets who had been styled and positioned and lit to within an inch of authenticity. Bardot looked like she’d just rolled out of someone’s bed, decided cinema might be amusing for an afternoon, and wandered in front of a camera still wearing yesterday’s desire on her skin.

The body that launched a thousand fantasies moved with balletic grace—a remnant of her disciplined training—but without the restraint that discipline usually imposes. She was paradox embodied: trained yet wild, aristocratic yet earthy, available yet utterly unreachable. Men didn’t pursue Bardot on screen; they orbited her, satellites caught in a gravitational field they couldn’t name.

And women? Women watched something shift. Here was permission they hadn’t known they needed—to want openly, to move through the world as desiring subjects rather than desired objects. Simone de Beauvoir, that architect of feminist thought, saw it immediately: Bardot had reversed the ancient equation. For perhaps the first time in cinema, the male gaze met its match in the female gaze that looked back, assessed, and chose.

The Gilded Cage

But gods and goddesses have always been prisoners of their own divinity.

The adoration that elevated Bardot—the magazine covers, the breathless coverage, the photographers who stalked her like prey—also suffocated her. Every breakfast became a photo opportunity. Every love affair became public property. Every private grief was extracted, examined, and sold back to her as entertainment. The sex goddess who had seemed so free was revealed to be the most trapped woman in Europe, unable to walk down a street, unable to age, unable to be anything other than Brigitte Bardot, eternal object of desire.

She attempted escape through the usual routes—marriage, motherhood, different lovers—but the machinery of fame had no reverse gear. Depression descended. Suicide attempts followed, reported with the same prurient fascination as her romances. The woman who had seemed to embody life at its most vital was quietly dying inside the image that had consumed her.

Film sets, which had once seemed like playgrounds, became torture chambers. She was bored by acting, impatient with the technical demands, exhausted by the repetition. Yet she was brilliant when she chose to be—brittle and devastating in The Truth, existentially wounded in Godard’s Contempt, anarchically alive in Viva Maria!. But these were performances extracted from someone who increasingly wanted to disappear.

At thirty-nine, she did.

No farewell tour. No carefully orchestrated final role. No transformation into character actress or elder stateswoman. Brigitte Bardot simply walked away from cinema as if shrugging off a coat that no longer fit, and the world that had made her could barely comprehend it. How dare she? How dare she rob them of the pleasure of watching her fade, of consuming her decline, of the slow erosion that celebrity culture demands as payment for adoration?

The Second Life

What came next was stranger and more uncompromising than anything she’d done on screen.

Bardot redirected the full force of her celebrity toward animals—creatures who, like her, were beautiful and trapped and subject to human cruelty. She founded an organization, sold her jewels, liquidated her possessions, and became as notorious for her activism as she’d once been for her sensuality. If she’d brought ferocity to desire, she brought it doubly to this new crusade.

But the same refusal to compromise that had made her revolutionary now made her radioactive. Her campaigns against religious slaughter practices, particularly targeting Muslim and Jewish communities, crossed lines repeatedly. Convictions for inciting racial hatred accumulated. Her alignment with far-right political figures hardened. The woman who had once represented liberation began to represent something darker—intolerance dressed in the language of compassion.

The contradictions were impossible to ignore and equally impossible to reconcile. Was this the same fearlessness that had revolutionized cinema, now turned rancid? Or had there always been something uncompromising in Bardot that could tip toward cruelty when unchecked? She insisted her only allegiance was to animals, but her rhetoric often suggested otherwise, bleeding into xenophobia and cultural chauvinism that alienated former admirers.

She aged publicly, defiantly, refusing the surgeries and erasures that celebrity culture demands of its women. Her face, which had launched an erotic revolution, became weathered and hard. She lived in isolation, surrounded by rescued animals, having traded one form of imprisonment for another—but this one, at least, she’d chosen.

The Goddess Unbound

There will never be another Bardot, and perhaps that’s mercy.

She existed at a precise intersection of cultural forces—the last gasp of European cinema’s golden age, the first tremors of sexual revolution, the birth of modern celebrity—that can never be replicated. She was analog in an increasingly digital world, instinctive in an age that would come to value calculated personal brands.

What she proved was both liberating and terrifying: that a woman could be utterly central to culture without asking permission, and could abandon that centrality without explanation. That desire could be wielded as power rather than vulnerability. That the price of being worshipped as a goddess was the loss of permission to be human.

She wanted to be remembered for her work with animals, not for her body or her films. History, characteristically, has refused to grant her that wish. We insist on holding all of her at once—the revolutionary and the reactionary, the liberator and the provocateur, the sex symbol who demolished sex symbols and the activist whose compassion curdled into rage.

Bardot died at ninety-one, having lived exactly as she chose: without apology, without nostalgia, without ever softening herself for an audience’s comfort. She was magnificent and maddening, liberated and lost, a goddess who spent her second life trying to escape the mythology of her first.

The cage she built for herself in her later years—filled with rescued animals rather than adoring crowds—was still a cage. But it was hers. And in the end, perhaps that was the only freedom that ever mattered to her: the right to choose her own prison, to define her own terms, to be both revered and reviled on no one’s authority but her own.

The sex goddess became the hermit. The icon became the outcast. And Bardot, to the very end, remained exactly what she’d always been: uncontainable, uncompromising, and entirely herself.

Disclaimer: The opinions and views expressed in this article/column are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of South Asian Herald.