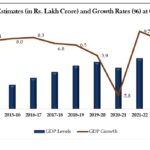

India’s stock market is riding the strongest wealth-creation wave in its modern history, yet the foundations of this surge are far less stable than the headline numbers suggest. Motilal Oswal’s 30th Annual Wealth Creation Study, often treated as a barometer of long-term structural trends, argues that the country may be entering a multi-trillion-dollar expansion that could take the economy from $4 trillion today to more than $16 trillion by 2042.

But buried beneath the upbeat projections is a more complicated picture—one in which high growth, surging financial wealth and booming consumption sit uneasily alongside risks that are growing just as fast.

The five years from 2020 to 2025 created an unprecedented ₹148 trillion in shareholder wealth—an annualized jump of 38% that no previous study period has matched. Much of this was triggered by the pandemic crash of March 2020, meaning the base itself was unusually depressed. Telecom and banking giants dominated the list of wealth creators, while capital-market firms—especially the BSE—posted astronomical returns driven almost entirely by a flood of retail investors. Nearly 150 million Indians now hold demat accounts, a number that would have been unthinkable before COVID-19. On the surface, this looks like the beginning of a durable financial deepening. In reality, it is also the biggest concentration of market risk the Indian household sector has ever carried.

The study tries to extract long-term lessons by identifying “compounders”—companies that sustained above-market returns for nearly two decades. Only 35 stocks survived a strict set of filters, reinforcing the point that genuine long-term winners are extremely rare. Most were consumer-facing businesses or early market leaders with high return ratios in 2008. But assuming this pattern will continue in the future feels optimistic. Many legacy leaders now face technological upheaval, regulatory tightening, climate-linked disruptions, and intense global competition. The past may not be the reliable guide the study implies, especially in sectors where the moat is shifting from scale to innovation.

India’s future growth hinges heavily on one pillar: credit. The banking system, after years of cleaning up bad loans, is arguably healthier than at any point in the last 20 years. Retail borrowing is rising rapidly, and NBFCs are reaching deeper into semi-urban and rural markets. The study projects that credit will expand faster than GDP for years, pulling consumption and investment with it. What it downplays is the emerging vulnerability beneath this expansion. Unsecured loans are rising at double-digit rates, household leverage is climbing from a historically low base, and fintech-driven credit models remain largely untested across a full business cycle. If growth slows or unemployment rises, the next NPA cycle may not be as benign.

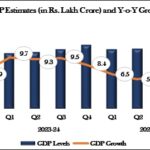

Capital markets, too, stand at a delicate intersection. The explosion of retail participation has created a thick cushion of domestic liquidity, often muting the impact of foreign outflows. But the reliance on retail flows cuts both ways. A prolonged correction could trigger a negative wealth effect—precisely the reverse of the GDP boost the study calculates during good times—sapping consumer demand at a moment when India’s consumption-led growth needs stability, not shocks. The country now has a market-cap-to-GDP ratio of 1.3x, higher than several larger economies; this is a sign of financial maturity, but also of valuation vulnerability.

The report’s consumption forecasts rely heavily on rising per-capita income and a China-style surge in discretionary demand. This projection assumes inflation stays contained, job creation keeps pace with household aspirations, and global commodity cycles remain manageable. Yet India’s labor market remains structurally fragile, with manufacturing still struggling to generate the number of jobs required for middle-income transition. Climate volatility—from heatwaves to crop-damaging rainfall—is already eroding rural incomes. These pressures will not simply “normalize” as the study seems to suggest. They could slow the pace of discretionary consumption just when the economy expects it to accelerate.

Even the macro-optimism has blind spots. The assumption that India’s GDP will quadruple rests on stable geopolitics, uninterrupted capital flows, a benign global interest-rate environment, and energy security in a world that is anything but predictable. India’s dependence on imported crude, its exposure to global supply chains, and the uncertain pace of the energy transition all present risks that compound over time. Fiscal pressures are another underplayed threat. As the government balances welfare spending with infrastructure ambitions, the room for error narrows. A decade of high capital expenditure will require stable revenues that may be difficult to secure if growth sputters or oil prices rise.

The study’s central idea—that India is on the cusp of a multi-trillion-dollar wealth expansion—is not unfounded. Demographics, rising savings, and formalization provide undeniable structural momentum. But the next 17 years will not resemble the previous 17. Growth will be faster, but also more fragile. Markets will be deeper, but more exposed. And while capital will compound for those who navigate these shifts carefully, it will also punish complacency with far greater force.

India’s wealth-creation engine is accelerating—but so are the risks around it. The challenge is not whether the country can reach $16 trillion, but whether it can do so without stumbling on the very vulnerabilities this study only briefly acknowledges.