Henrik Syse is an eminent philosopher, author, and former Vice Chair of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, which awards the Nobel Peace Prize. He served a full six-year term from 2015 to 2020 as a member, and later as Vice Chair of the Norwegian Nobel Committee. He has also taught cutting-edge courses about war and peace, inspired by Nobel.

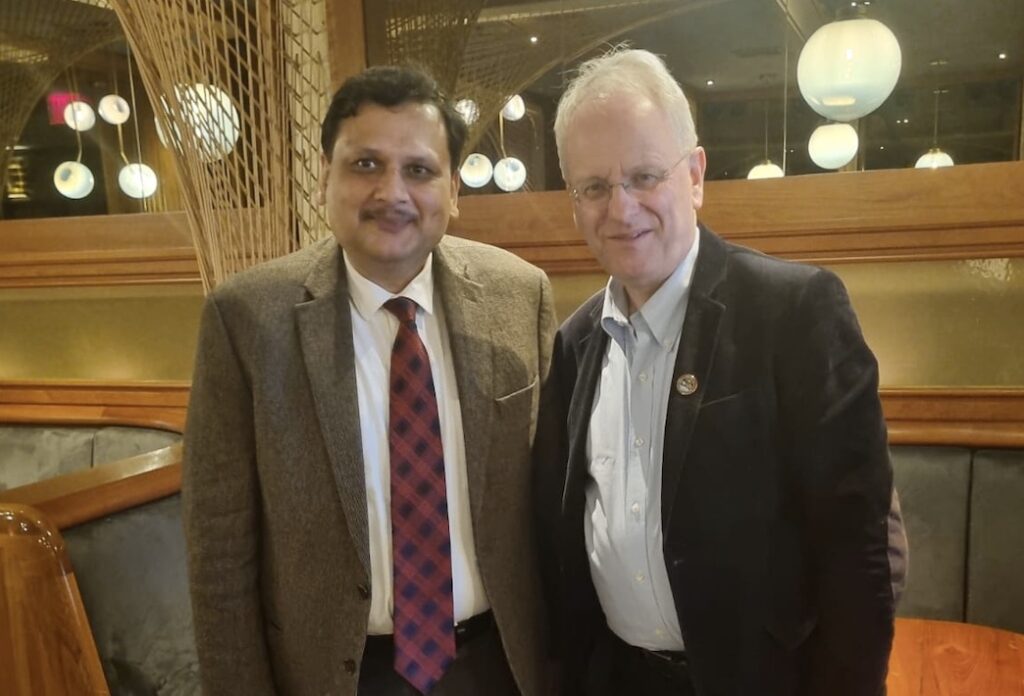

In this exclusive conversation with South Asian Herald, Syse talks about morality, diplomacy, human rights, climate politics, ethics, and investment. Through his work, Syse challenges future leaders to follow not only logical but also ethical conduct for a more just and meaningful world and for social advancement.

Syse is also a research professor at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) and professor of Peace and Conflict Studies at Oslo New University College. He is a specialist in the ethics of war and peace and has authored and edited many publications spanning philosophy, politics, business, religion, war, and ethics.

He previously served as Head of Corporate Governance for Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM), which manages Europe’s largest sovereign wealth fund.

Religion, War and Ethics

Reflecting on his co-edited book, Religion, War, and Ethics: A Sourcebook of Textual Traditions, Syse addresses the demanding idea of an “ethically correct war.” He states that a “perfectly just war simply does not exist.” However, he firmly believes that “there can be more or less justice in war.”

According to the just war tradition, which he notes is reflected in most world religions, sound moral philosophy can guide us towards an ideal, covering both jus ad bellum (the right to go to war) and jus in bello (conduct in war). Syse emphasizes two core tenets: “war must always be a reaction against aggression, and war must never be chosen as a means when reasonable peaceful alternatives exist.” Furthermore, he stresses, “indiscriminate means of war that cause large-scale destruction of civilian life and property must not be used.”

Geo-economics and Ethical Investment

When defining ethical investment, Syse explains it as a strategy that takes environmental and social concerns seriously and integrates them into investments. This approach is rooted in the belief that “severe damage to the environmental or to the social fabric of society is deeply problematic for most investors in the long run.” Investments that contribute to poverty and environmental damage can be damaging to one’s reputation and long-term earnings. In addition, of course, they are morally problematic in themselves.

The marketplace, however, is also driven by competition and the need for profits, sometimes creating significant dilemmas. The central conflict, he notes, is “the one between short-term and long-term social and economic gains.”

Giving up current stability for longer-term needs often comes across as unappealing to many. To resolve this, Syse calls for a “sustained dialogue about this very tricky balance,” and that dialogue must be global, especially to prevent national and corporate interests from “totally trumping ethical concerns, not least when it comes to human rights.”

Climate Justice: Navigating the Global Green Transition

Addressing the tension between developed nations, which often rely on fossil fuel exports, and developing nations on environmental issues, Syse warns that “stern lecturing from developed nations can be problematic.” He urges global cooperation that accounts for social needs and recognizes the “responsibility that many of the world’s richest countries carry for our climate and environmental crises.”

He maintains that fossil fuel exports are not inherently immoral, given that “so many social and economic gains in our world have historically come from the use of fossil fuels.” While the desire of profitable countries to fund a green transition should be welcomed, it must be managed “in a way that does not punish the world’s developing and emerging economies.” Ultimately, he said the focus must shift from “pure blame games” to concentrating on common goals and sustainable justice through respectful diplomacy, collaboration, and dialogue.

AI, Autonomous Weapons, and the Role of the Nobel Peace Prize

On the emerging landscape of AI, automated drones, and cyber weapons, and whether they can play a role in the selection of future Nobel Peace Prize laureates, Syse acknowledges that political trends and developments “always play a role in the deliberations of the Nobel Committee.”

He highlights a critical ethical boundary in future warfare: the need to ensure that “we don’t deploy weapons that cannot be properly controlled by human means or by the law of armed conflict.” Individuals and institutions fighting for this vital aim of human control over lethal autonomous systems may indeed be “worthy recipients of the prize at some point.”