For millions of Indians working abroad, trips back home are often planned around family needs — ageing parents, weddings, medical care or festivals. A recent ruling by India’s income tax tribunal may now force many of them to count their days far more carefully.

In a January 9 order, the Bengaluru bench of the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal (ITAT) ruled against Flipkart co-founder Binny Bansal in a case that tax experts say could reshape how residential status is determined for Indians employed overseas.

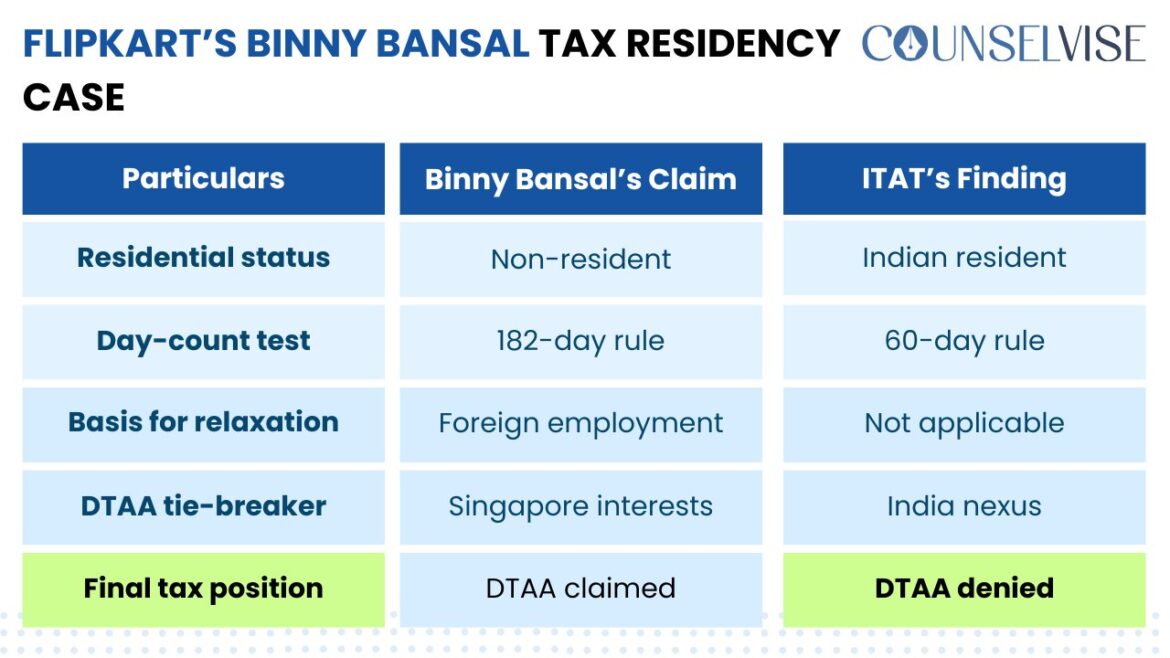

The tribunal held that Bansal could not claim non-resident status for tax purposes despite living abroad, and denied him relief under the India–Singapore Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement. While the case involved high-value share sales, its interpretation of India’s residency rules could affect a much broader cross-section of the Indian diaspora.

Why the ruling matters

Under India’s Income Tax Act, residential status is not based on citizenship or domicile but on physical presence in India. Normally, an Indian citizen working abroad can spend up to 182 days in India in a financial year without becoming a tax resident.

However, the tribunal ruled that this extended 182-day threshold applies only if the individual was already a non-resident in previous years.

“This decision effectively penalizes people who leave India later in the financial year,” said Ved Jain, a tax expert who has analyzed the order.

According to Jain, an Indian who leaves India for overseas employment on or after October 2 will typically remain a resident in the year of departure because they would have already spent more than 182 days in India. More importantly, in subsequent years, even a visit of 60 days or more could trigger resident status — and tax liability on global income.

“In practical terms, such individuals may not be able to spend more than 59 days a year in India for several years after moving abroad,” Jain said.

A tale of two departure dates

The ruling draws a sharp distinction based solely on the date of departure.

An individual who leaves India before October 2 would usually qualify as a non-resident in the year of exit, provided their stay is under 182 days. In later years, the law allows them to visit India for up to 182 days without losing non-resident status.

But someone who leaves after that date could face tighter limits on visits back home, even if their work, income and tax residence are clearly overseas.

“This creates two categories of overseas Indians — those who left before October and those who left after — even though their circumstances may otherwise be identical,” Jain said.

The Binny Bansal case

Bansal had argued that he was residing and working in Singapore during the relevant financial year and should be treated as a person “being outside India” who came to India only on visits. He claimed exemption from Indian capital gains tax on the sale of Flipkart shares under the India–Singapore tax treaty.

The tax department rejected this, arguing that the relaxation in the law applies only to those who are already non-residents. The tribunal agreed, saying that accepting Bansal’s interpretation would allow residents to repeatedly extend the relaxed threshold simply by asserting overseas residence.

The tribunal dismissed Bansal’s appeal but asked tax authorities to process a pending refund of more than ₹5.8 crore, if not already issued. Bansal may challenge the ruling in a higher court.

Legal debate continues

Jain said the ruling departs from a literal reading of the law by equating the phrase “who being outside India” with “who being non-resident”.

“That interpretation is debatable and may not be the final word,” he said, adding that higher courts could still clarify the position.

For now, tax advisers say Indians working overseas — particularly in the Gulf, Southeast Asia, Europe and North America — may need to plan India visits more cautiously, especially in the first few years after moving abroad.

For many in the diaspora, the judgment underscores a simple but uncomfortable message: the timing of when you leave India may matter almost as much as where you live afterwards.