“Poaching the best and ignoring the rest” appears to be the emerging immigration mantra of the developed West as it moves into 2026. The message to countries rich in manpower, both skilled and unskilled, is increasingly explicit. An elite group of nations, among the most sought after by prospective immigrants, has been steadily tightening borders to reduce what they describe as “infiltration.”

Alongside these restrictions, several of these countries have initiated both legal and inhumane deportation processes to remove what they term “dead wood,” arguing that their ageing populations have already met domestic workforce needs.

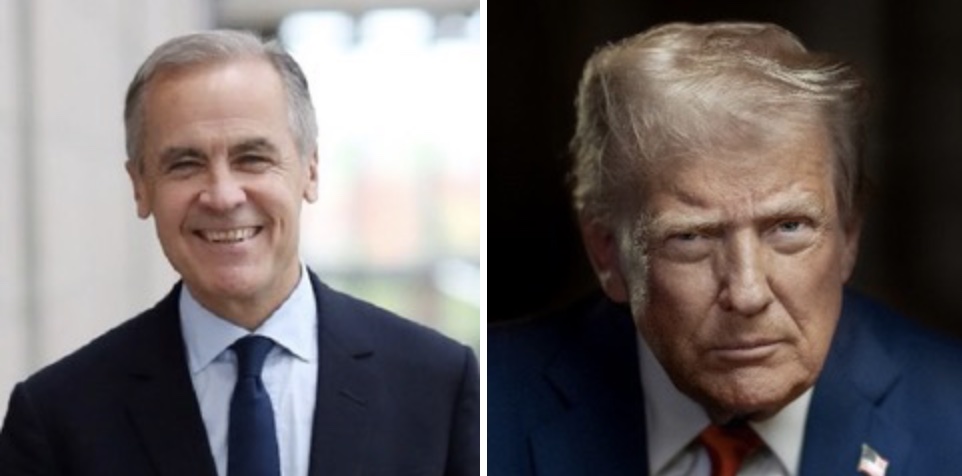

When the new Liberal government led by Mark Carney assumed office in April 2025 and presented its first budget in November, it signaled a clear shift in policy, stating that it would “look for the best of brains” to lead new scientific research initiatives. Under mounting pressures, the government not only reduced overall immigration targets but also introduced sharp cuts to international student intake. This significant change in immigration policy has dashed the hopes of hundreds of thousands of young people aspiring to settle in developed Western nations. For those without specialized skills, immigration pathways are now effectively closed.

In the United States, President Donald Trump, soon after beginning his second term in January 2025, launched large-scale deportations using U.S. Air Force aircraft stripped of basic passenger facilities. Undocumented immigrants were sent back to their countries of origin, including India, and the process has continued without pause. Hundreds of thousands have been deported in this manner, with flights regularly departing from North American ports to destinations across South Asia, Africa, and elsewhere. Notably, those deported do not include highly skilled professionals such as doctors, engineers, or scientists.

The closure of these migration channels has had consequences beyond individual lives. For many developing nations, emigration had helped ease pressure on limited job markets and public resources. With this outlet narrowing, pressure is rebuilding rapidly. While top talent continues to leave, these countries are left to manage large populations with shrinking employment opportunities under tightening global economic conditions.

The brain drain, meanwhile, shows no signs of slowing. Training a doctor in a government medical institution in India over six to eight years costs the state a minimum of Rs 20 lakh. Comparable public investment is made in engineers and IT specialists trained at government institutions. Yet once these professionals graduate, developed nations actively recruit them. Instead of repaying the society that funded their education, many leave their homelands, drawn by better opportunities abroad.

The consequences are visible at home. Shortages of doctors, engineers, technocrats, and other professionals persist. Mental health care offers a stark example. Despite Supreme Court directives requiring a mental hospital in every district, fewer than 20 percent of districts have such facilities. India also faces an acute shortage of medical super specialists. In some cases, medical colleges reportedly inflate faculty numbers during inspections by temporarily drawing specialists from the private sector.

The impact extends beyond health care. Information technology, scientific research, engineering, and related fields continue to feel the strain of changing Western immigration policies.

India is also grappling with shortages of mid-level officers in its defense forces. Pay packages are often less attractive than those available to graduates of elite technical institutions, while many traditional perks of defense careers have diminished over time. The lack of guaranteed long-term careers under schemes such as the Agnipath Yojana has further reduced the sector’s appeal. In some cases, young people who avoided military service at home in pursuit of overseas opportunities have ended up joining foreign armed forces, as seen in Russia.

These developments underscore the urgent need for countries rich in human resources to reassess their own policies. Nations such as India must consider regulating both brain drain and the outflow of unskilled labor. This also calls for a thorough audit of domestic education and health care infrastructure. India, for instance, could position its education and health care capabilities as strengths rather than losing talent to the West.

Without such recalibration, developing economies risk continuing on the same path, losing their best minds abroad while being left to manage the rest at home.