It was the spring semester of 2010 at the University of Oregon, and I was a student of East Asian history; a curiosity-turned-passionate interest. In all my years as a student, I had never learned much of Asian history: I found it was ripe with folklore and historical contexts to world history I had never been taught. It was a breath of fresh air, and fanned the flame of my imagination—a flame that would eventually turn into my debut novel.

One particular anecdote that captured my attention was of phantom locomotives.

Meiji-Era Japan (1868 – 1912) is one of the most intensely studied time periods. It’s when the feudal lords fell, and the Emperor reclaimed the throne of power, bringing Japan back to an imperialist nation after hundreds of years. Until the 1850s, Japan had also been isolated with closed borders—by choice—since 1603. Their isolation ended when Americans and Europeans landed on an eastern Japanese shore, bearing a note that it was time for Japan to re-enter the world economy and rejoin society.

When Emperor Meiji ascended the throne, he was bombarded with requests from governments everywhere eager to work with him and reestablish trade routes. He took inspiration from: the United States to write Japan’s Constitution; the Europeans to form a Parliament; Western Asia for agriculture and weaponry; and the world at large for reshaping their nutrition, architecture, and clothing.

Technology was rapidly imported, ushering in Japan’s Industrial Revolution. The Japanese saw an introduction of gas and electricity, telephones and telegraphs, engines and locomotives all in ten short years, changing their lives almost overnight. Locomotives connected the Japanese cities, unifying them more than ever, and changing the way the Japanese traveled, transported materials, and communicated.

Before written laws protected employees from long hours, conductors were expected to drive the trains for as long as the route lasted, even if it amounted to working twelve-, fourteen-, or even longer, hour days. The darkness and remoteness spurred delirium. Many recounted that they often saw ghosts in the shapes of trains which would disappear just before collision. These apparitions caused them to slam on the brakes to avoid accidents, sometimes leading to damaged engines or delays in delivery. But nobody could explain the appearances of these ghost trains—except through folklore.

Back in college, stories like this fascinated me. I hadn’t heard of folklore and ghosts being included in history as if it were a fact. I had never heard of such phantoms appearing on Western railroads or Amtrak. But I also didn’t have enough knowledge to understand why this felt like a natural occurrence in Japan.

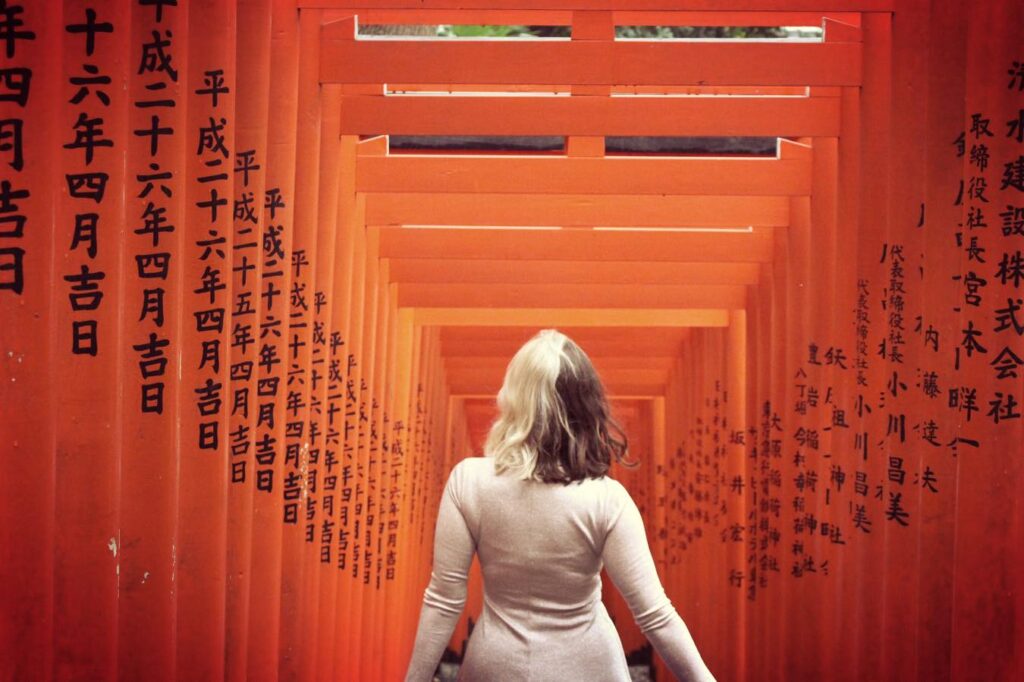

Upon graduating, I moved to Japan, where I furthered my education, worked a number of jobs, and resided for nearly six years, across Hokkaido and Tokyo. All the while, there was a story of a train chugging along in my head. As I traipsed across the country as a journalist, reporting on: the rebuilding in the wake of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, rights of foreigners living abroad, the campaign to amend stringent drug laws, sake made from sweet potatoes, and sparkling illumination around the holidays, I was collecting insights, perspectives, and voices that fed into crafting my first novel: Ghost Train.

Ghost Train is a folk-horror novel set in 1877 Kyoto during Emperor Meiji’s rule during the Industrial Revolution. Based on true events and folklore, samurai daughter Maru Hosokawa spends the summer working in a geisha teahouse where she is haunted by: ghosts, plagues, and a mystery surrounding disappearing girls. A kitsune, a fox-shaped demon, finds her and claims the faults lie with the emperor, urging her to help before she too falls victim. Maru overcomes her anxiety and finds the strength to confront authority while challenging the rapid transformation and Westernization of her society—her mission is to save her world while simultaneously finding her place in it.

It’s a historical account of the tumultuous time period I first began studying over a decade prior. While living abroad in Japan, each friend, coworker, and person who I met imparted a little of themselves, their family histories, and their story onto me. Suddenly, after six years, I found myself carrying around a wealth of knowledge and insights of this nation that had become a second home. I wanted to put it somewhere, and treasure the memories and the generational tales I had collected. Then, I went back to the story of those phantom locomotives. I paired it with all I had observed: a changing nation, one-fifty years later, still evolving, still advancing in technology, and still ever-popular globally for its art, food, culture, and mystique. I thought about all of the superstitions from the Meiji Era my friends’ grandparents told to them, all of the thousand-year traditions I witnessed. Suddenly, the phantom locomotive became a metaphor for a society confronted with inventions and innovations, and balancing how to hold on to their old traditions while catering to a demanding and progressing world. I put words to paper, and Ghost Train sprang to life.

Though I had since returned to the United States, I wanted to retain an authenticity that would be found in Japanese literature and art. I collaborated with historians and subject matter experts across Japan and the U.S. for historical accuracy. It was critical that I not only rely on my personal experience in Japan, but others’ perspectives, knowledge, and expertise. In true journalist fashion, I interviewed monks, maiko (practicing to be geisha), astrologists, language experts, and more. I treated this book, though a work of fiction, as I would an academic essay or an article, and did my due diligence, intending that people can come away from reading Ghost Train as having learned something new, and something true.

SelectBooks Publisher, Kenzi Sugihara, has had a long career in book publishing, including his stints as a Vice President and Publisher at both Bantam/Doubleday/Dell and at Random House, oversaw a number of best-selling and critically-acclaimed books. In response to what attracted him to my novel, he stated, “One of the many compelling things that we saw in Ghost Train was Natalie’s ability to assemble this fascinating tapestry of history, fantasy, and Japanese culture to produce an immersive story. I found it to be simultaneously thrilling and meditative. Also, her deep connection with Japanese culture is unmistakable, and quite profound.”

In his endorsement for the book, Jake Adelstein, author of Tokyo Vice and The Last Yakuza, stated, “With lyrical prose that evokes the mystique of 19th-century Kyoto, this meticulously researched narrative weaves together historical authenticity with the ethereal allure of yokai folklore. Prepare to be captivated by a world where every shadow conceals a mystery, every whisper harbors a secret, and every choice echoes in worlds seen and unseen—a mesmerizing journey that will linger in your thoughts long after the final page is turned.”

Ghost Train is just the beginning—of my career as an author, but also, a reader’s journey to understanding and learning about Japan and Asia. Behind the popular anime, manga, and Pokemon, is true history and folklore, often intertwined, sometimes interchangeable, but always told together. Ghost Train is my love letter to Japan, and I hope it opens the doors for so many more, like Japan did for me.

(Ghost Train is Natalie Jacobsen’s debut novel.)